Quilting and sewing were some of the few creative outlets available and acceptable for women in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Some women intentionally created works of art, while others created accidental art while they were going about the business of life.

In 2007, a cotton sack from the mid-1800s was discovered in a pile of rags. The bag, which contained “a tattered dress 3 handfulls of pecans a braid of Roses hair" and was “filled with my Love always” was a going away gift for 9-year old Ashley, who was sold away from her mother. This work, which is on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, evokes strong reactions from staff and visitors. (You can read much more about Ashley’s sack and the generations of women here.)

As Mark Auslander, director of the Michigan State University Museum, writes:

“This 1921 needlework emerges out of a long history of textile art in North America. Embroidering texts, including homilies, scriptural quotations, and short family histories, is a well-established practice in American decorative arts, undertaken by women since colonial times. Ruth’s act of embroidering her family story onto this precious heirloom is also akin to the long-established practice of quilting in African American women’s networks, stitching valued textile pieces associated with cherished relatives and ancestors into new amalgams that will pass on to their posterity. Indeed, many abolitionist women, white and black, sewed samplers depicting abolitionist images and quotations.”

Our students continued this long tradition. Their embroidery work, which incorporates elements from Toni Morrison’s Beloved and the Civil Rights movement, rejected or confronted or embraced. Students explored incomplete histories or multiple histories or simply questioned history. Students challenged or reframed or fractured or revised or amended or deconstructed.

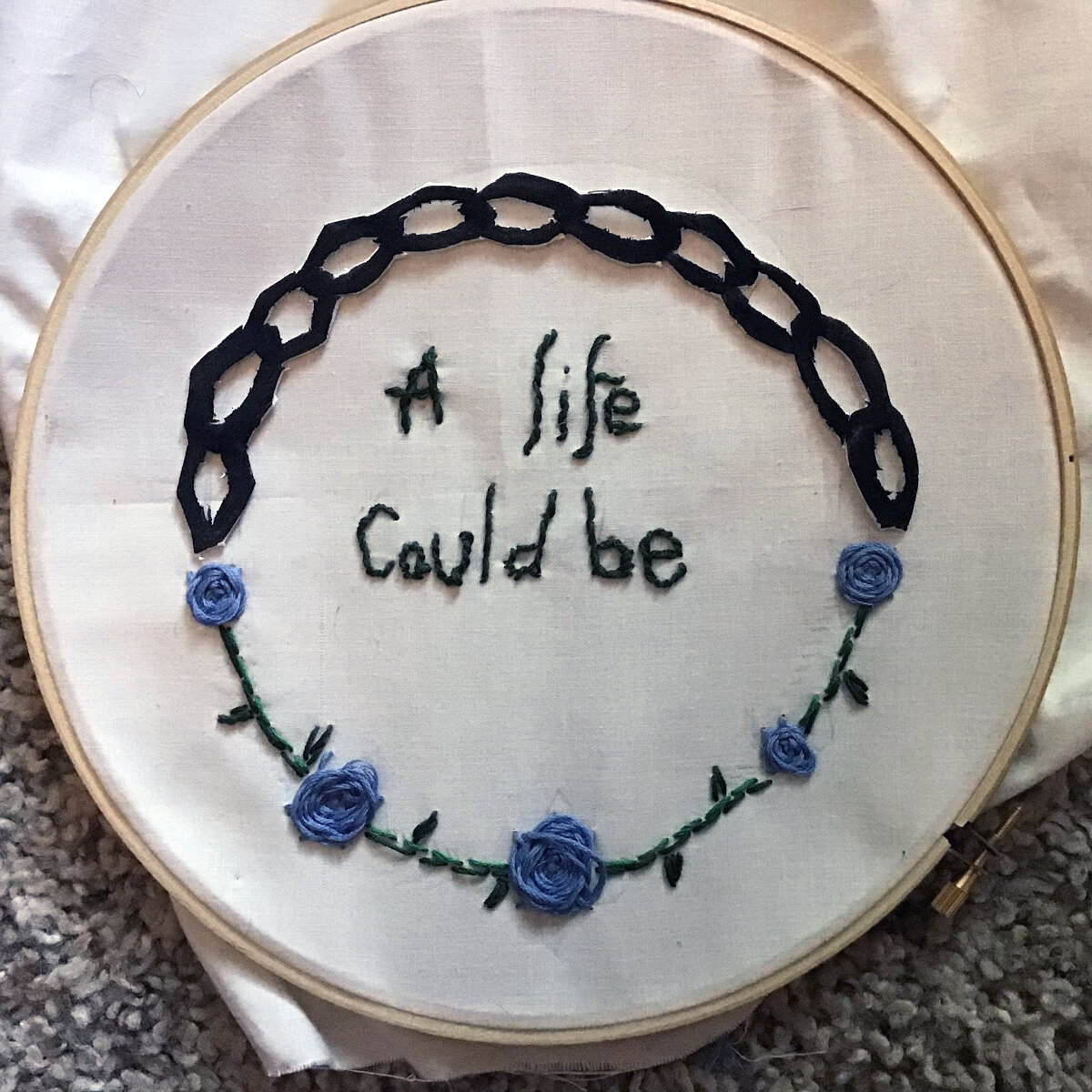

Maddie T. "Blood Roses" When I read in the book the quote that I ended up choosing, it immediately struck me. It was descriptive and emotional and I thought it would be the perfect representation for this project, so that’s why I chose to use it and then depict that scene in the center. The quote and scene relate to the general themes of the book for many reasons. Firstly, the violence depicted as beautiful. Sethe is described as having “roses of blood” that blossom on her shoulders. Morrison could have chosen aa number of other descriptors, but I think use of nature and its beauty fits with the way violence and pain is represented in the rest of the book, like an attempt to make the best of the bad situation or find the beauty in it. That’s what the little red-pink designs on the sitting figure are— Sethe, holding baby Denver, with the blanket around her shoulders and the “roses of blood” blossoming through. The figure behind her is Baby Suggs, and she’s wearing the quilt that she’s described as sleeping under during her final days. Sethe says that on that quilt there were only two places with color— two orange spots. I chose to represent those with the monarchs on the bottom edge. Monarchs are known for their long migrations in large numbers, and I wanted the monarchs to represent their exodus from Sweet Home and their long journey to Cincinnati, as well as the Underground Railroad and how many slaves had to make long trips to escape their masters. I think this scene is also important because it shows the generational grief of slavery; you have a mother-in-law caring for her daughter in law and her grandchild, three generations struggling with their own grief and the grief of others, all burdened by the same oppressive force. The chains around the outside are also meant to represent slavery and its tight hold on the family— it’s encircling them entirely, with no holes or gaps to escape. I chose to write the quote in a circle around the center scene in order to represent a halo, because Baby Suggs often had the title of “holy” after her name. The bead placement also has meaning: the interval in between the beads at the bottom and top is 28 chain links (the number of good days Sethe spent in Cincinnati), then 9 links before the next bead (the number of slaves who tried to escape Sweet Home that night), then 4, 2, and 1, to represent 124, and how of Sethe’s four kids, number 3, Beloved, is missing. Because as well as slavery, the chains represent Sethe’s life— all those numbers are a part of her story, and her story and life is inextricably tangled with the institution of slavery. As Sethe said, she can’t stop re-remembering, just like how she can’t escape her life as a slave even though she is now technically free.

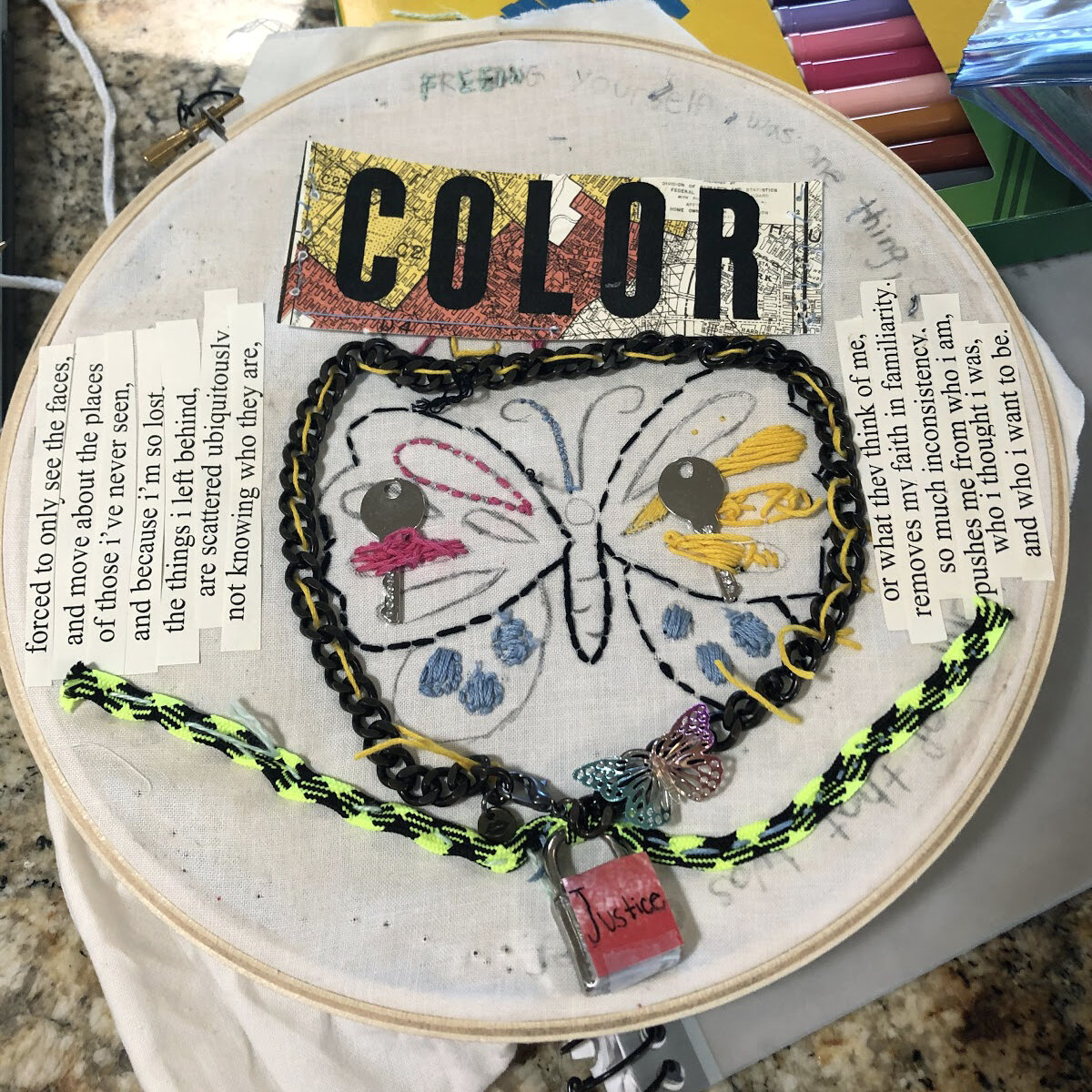

Alea L. untitled

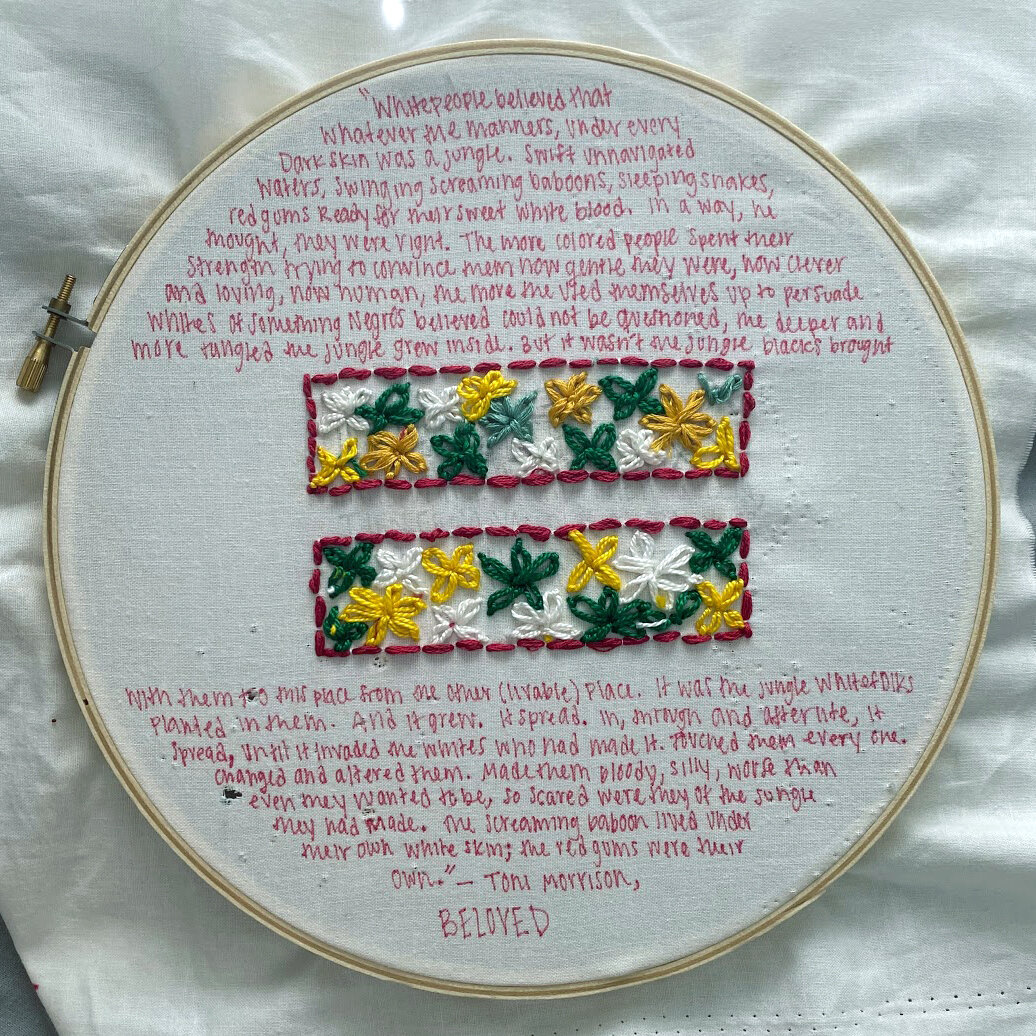

Alyssa K. "Stitches of Equality" In the very beginning of this project I set out to create the imagery that I saw in my head when reading beloved. Specifically the river, flower bed, etc. after my first attempt I realized I had a different vision for this piece I was creating. Once I started over I was on a roll. I started off with creating the equality symbol for African Americans. I outlined this in red for a number of reasons but really to symbolized the redlining that is still a huge issue today. Inside the symbol I wanted to put flowers because flowers symbolize new beginnings and I felt like after reading this book and learning what I have learned over the past two years about civil rights and slavery, has showed me we still need equality and we need to let go of the crazy laws and regulations that have kept us trapped in this cycle of inequality. We need to let go and find new ways of creating equality. As for the writing I really loved how this quote showed the evolution of the interaction between whites and blacks. Morrison talks about how blacks have to try and show the white people that they are actually human. I also found the jungle to be an impactful way of describing what the whites saw in the blacks because it created an image of this untamed savage. From this process I learned that it's ok to start over and evolve your ideas over time. I was so frustrated in the beginning of this project because I was having such a hard time knowing what i wanted to convey. I think in the end once I allowed myself to fail and restart, I was extremely successful. I love how this turned out because it really got my point across in a meaningful and artistic way. I am very glad I could finish up my time in IGSS creating something I am truly proud of.

Amber B. "Love Your Contrast"

Anna F. "Selective Focus" I began my embroidery by choosing a quote and then brainstorming imagery that could be connected to it. Then I sketched a pencil drawing directly onto my fabric and began to embroider. I wanted to include some nuance to my work to provoke thought and new ideas from the viewers, so that’s why my embroidery seems kind of random. The silhouette in white is in the spotlight, which gives it focus. The black silhouettes are hanging to a loopy design, and seem to be falling or relying on the support of the other black silhouettes. This signifies the majority of racial violence and hatred that does not get addressed by the media, and how these stories can barely cling to the structures that would bring them to light. The leaves symbolize the growth that these stories can have in the media, the growth of the dismissed racism in our society, and once they shrivel up and die, the death of racial justice and equality that our nation is facing today. The colors of the figures also give light to the people and stories that are prioritized in the media and news. The main ideas and themes I tried to cover were racial violence, racism in general, media attention and recognition, ignorance, forgetfulness, and privilege. I am happy with my embroidery because I feel like I really challenged myself creatively and ideologically during the entirety of this process. I learned that it’s normal and acceptable to evolve original ideas into new ones, even midway through the process. I am proud of my work, and I feel my work was successful. I am very happy with the way the execution of both the embroidery and the thought processes turned out. I have never embroidered anything before, but I’m so happy bout this assignment because I found a new passion for embroidery!

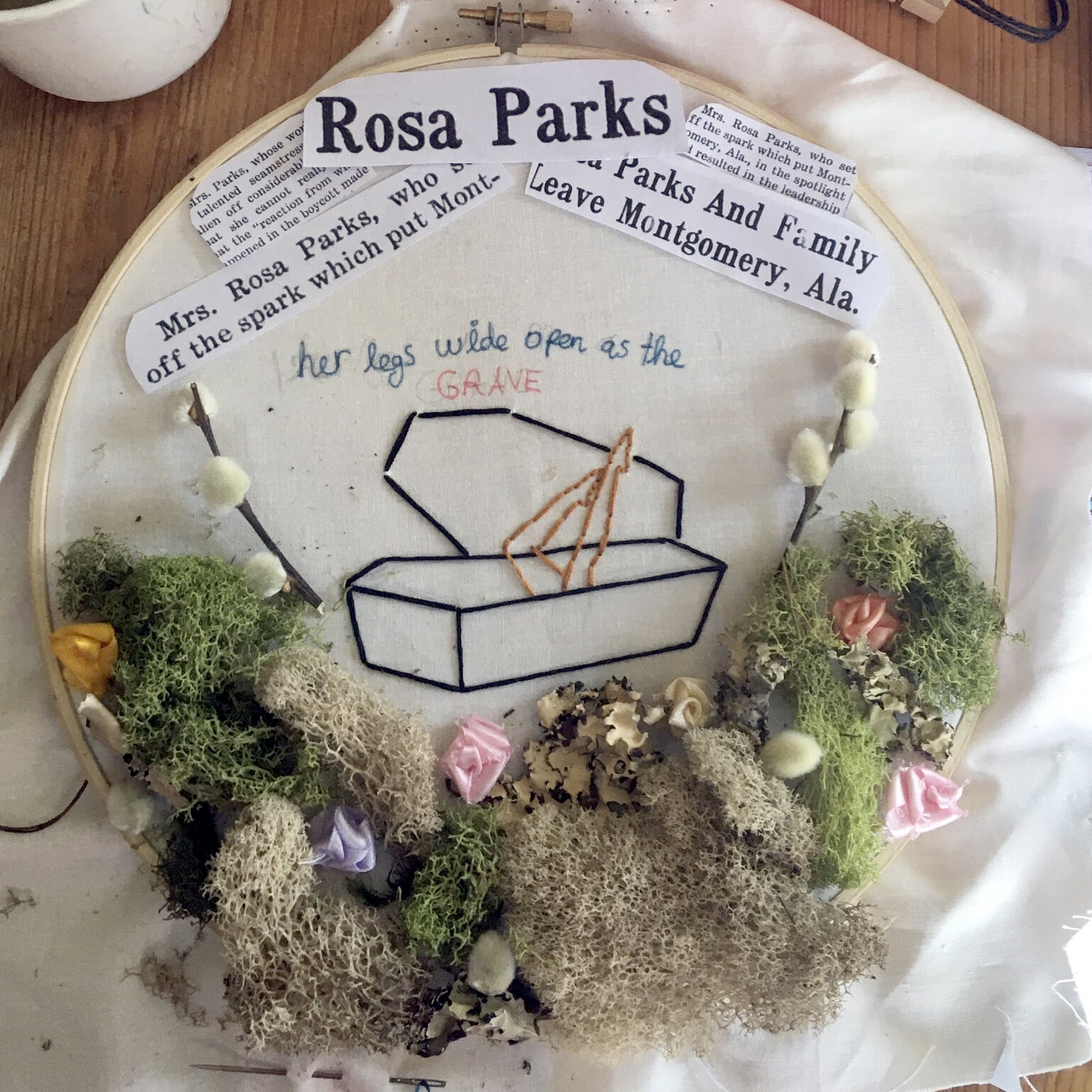

Anya P. I just did what I thought looks pretty. I tried to tie I’m Rosa Parks and the emerald closet. I abused the other materials, I just did what I wanted to.

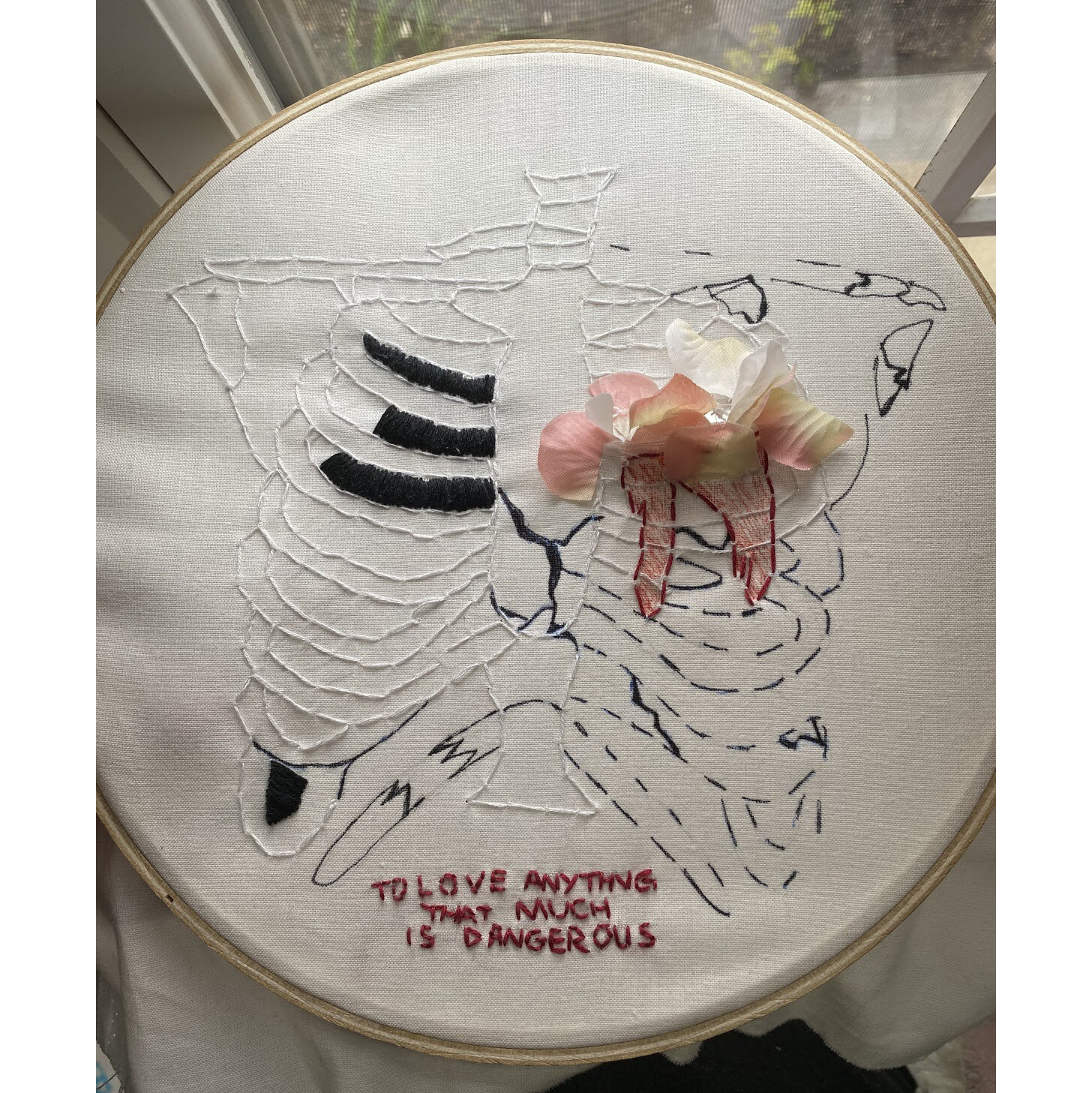

Cate C. "You Deserve as Much Love as You Give Others" The main ideas of my artwork was basically to emotionally tell a story of pain and trauma. I thought a human rib cage was a perfect way to get a human touch in the matter, and make it more grounded to us. However, it isn’t a complete breastplate but rather a broken unfinished one. To me, trauma breaks individuals and makes them feel less than whole. Reading Beloved, I felt like Beloved’s emotions were portrayed in that way. Beloved herself felt empty and sought for Sethe’s love and care because of all the burdens she carried with her. Although from the start, I intended to fill everything in but was met by challenges of getting floss, I thought the simplistic nature in the end actually highlighted the broken parts very well with the use of pen. It almost feels like we’re looking into someone’s inner skeletal structure and finding all these cracks, bruises and holes of what once was a whole person. The flowers are not only there to represent its intended meaning, it is also there to give life to what is overall a very somber piece on human emotions. The blood though shows a different kind of emotion, one of pain and suffering from keeping within oneself for too long and letting themselves love others too much and not caring for themselves. My quote also does a great job putting it into words. I didn’t like my final product at first but have learned to love it! It highlights all that I need to highlight in an impactful way Overall, the process of embroidery was fairly more difficult than I thought (even for being a seamstress). I started off very strong and even much earlier than it was assigned (so I got a head start. Not many pictures unfortunately!) but then dropped off later on as my materials kept cutting short. Still, I found ways to still portray my art across and have fun with it. I enjoy embroideries aesthetics and will be continuing it on my own time when I’m stressed or feeling down.

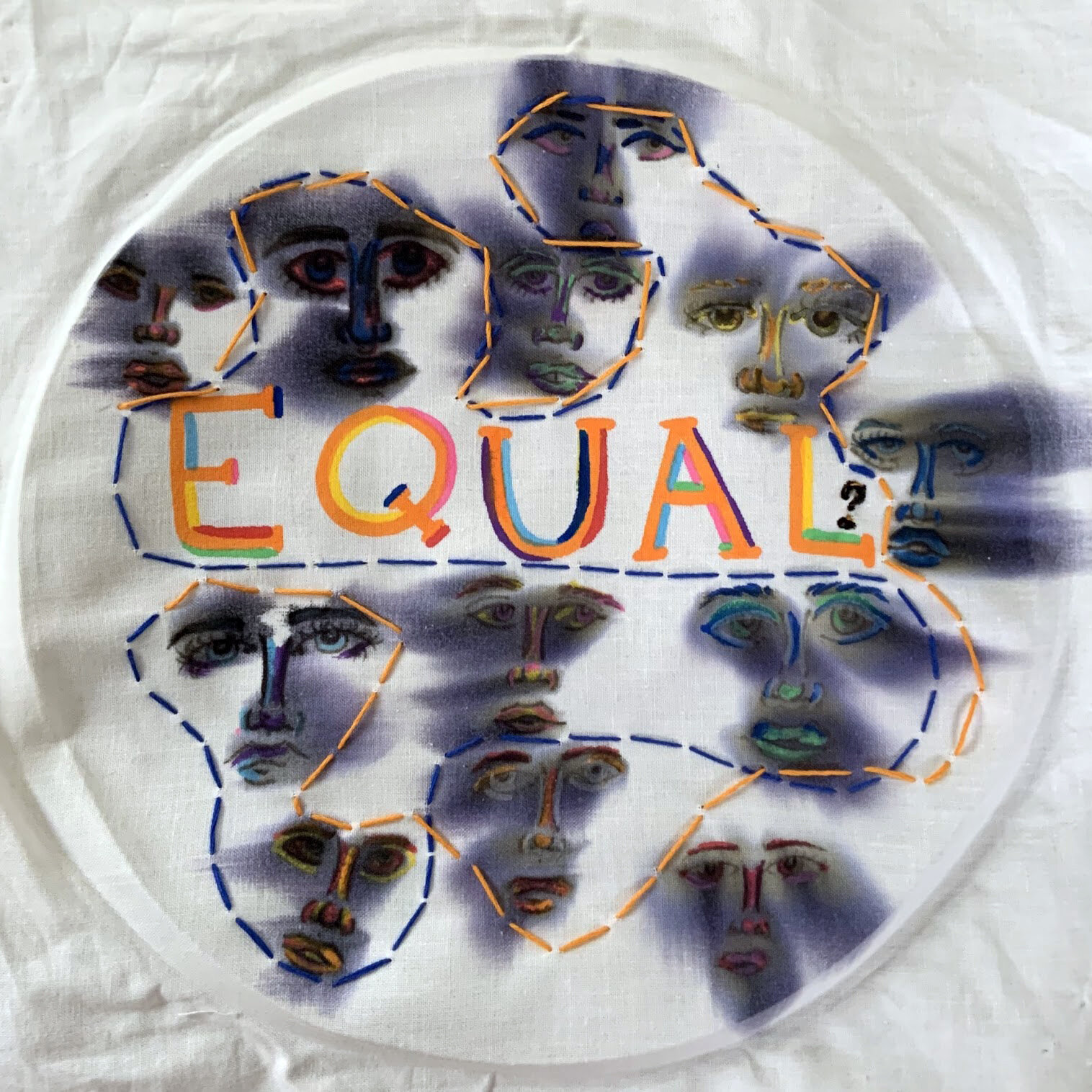

Chloe B. "Equal" I hoped to create an image that is fighting for equality. I drew faces in different colors to show that everyone is different, but they each deserve the equality that they yearn for. I later faded those faces with water to show that their equality is faded and isn’t always something that each individual can hold onto. I embroidered lines to represent the fight for equality. The curving dark blue line is discrimination that surrounds each human. The sharp orange line displays a fight for equality, facing the blue line in different areas and wrapping itself around the blue. The main idea of this piece is that equality is something that will always have to be fought for. I believe that I was successful in creating the main idea that I wanted. I learned that embroidery is very different than drawing and needs to be approached differently. I spilled water on one of the faces by accident right before progress picture #3. This gave me the idea of fading equality, so I sprayed water on each face after. This assignment was a difficult learning process for me, but I would not have learned what I did about my theme without it.

Chloe O. untitled

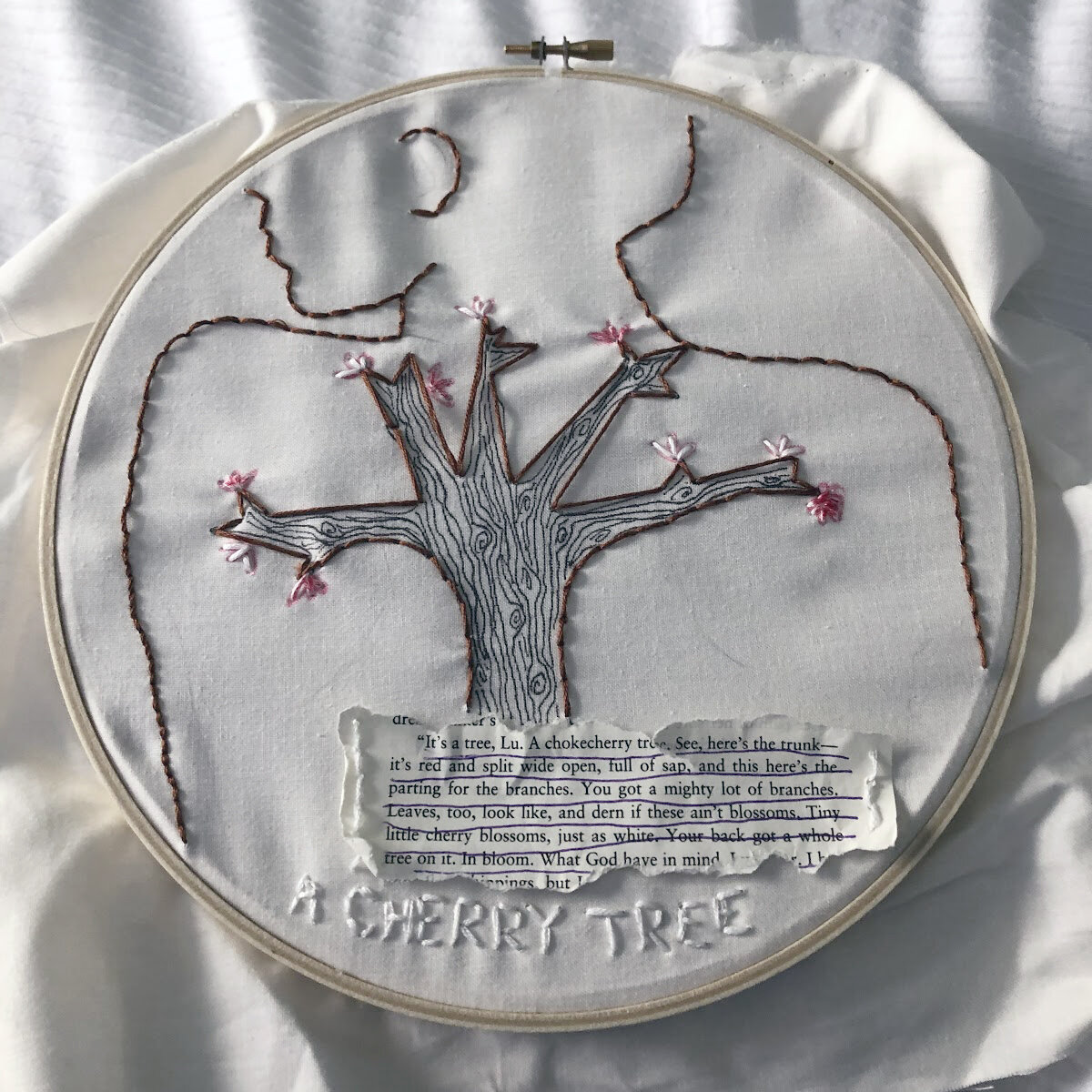

Cori W. untitled the main importance of the embroidered picture is the tree. the tree represents sethes scars and how they were compared to a cherry tree, so i decided to make them a cherry tree. I also chose not to fill the back in with color to show that when people look at her back they don’t see her they see her scars. i also chose to rip the quote out of the book because i really liked the look of the ripped paper and how i underlined it when i first read it.

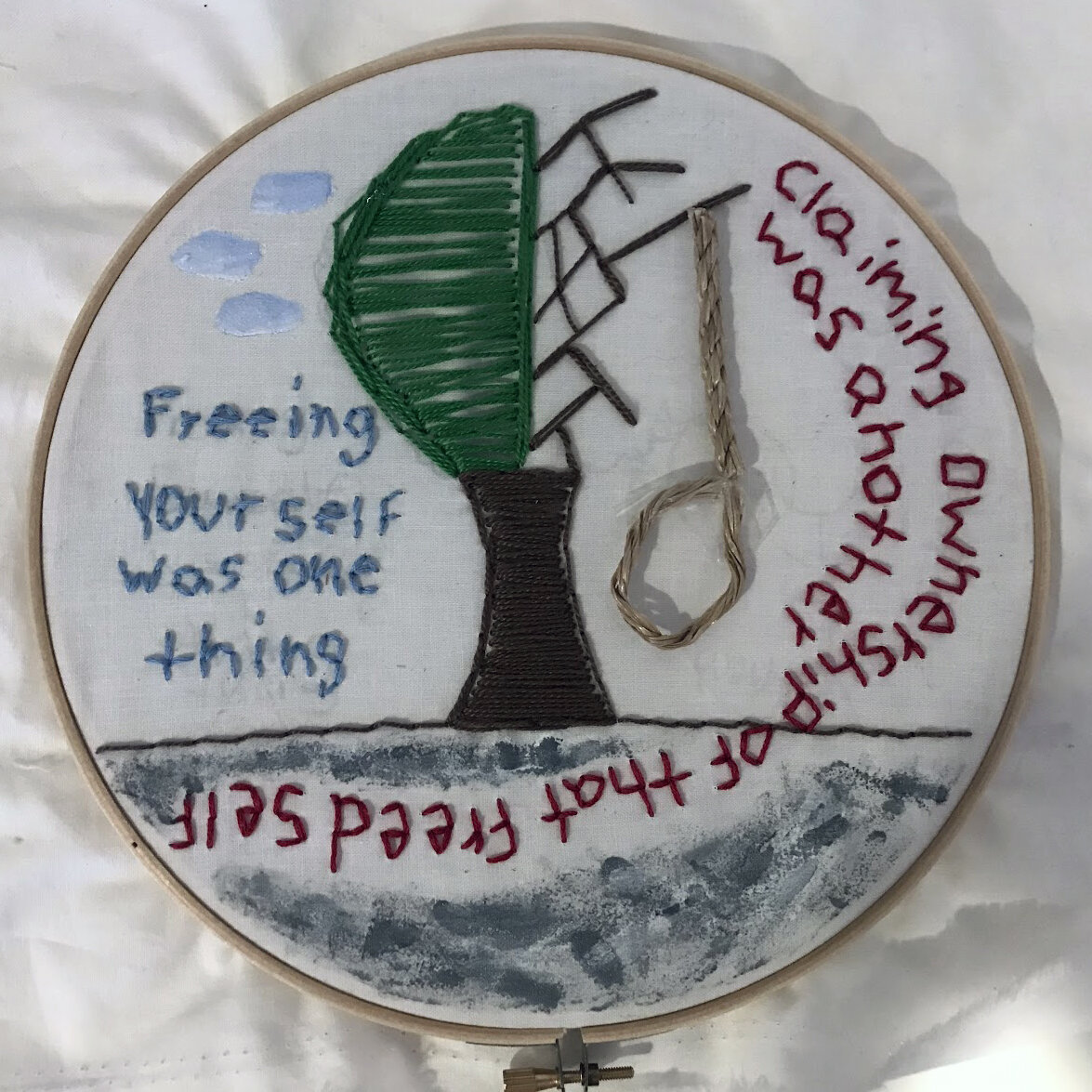

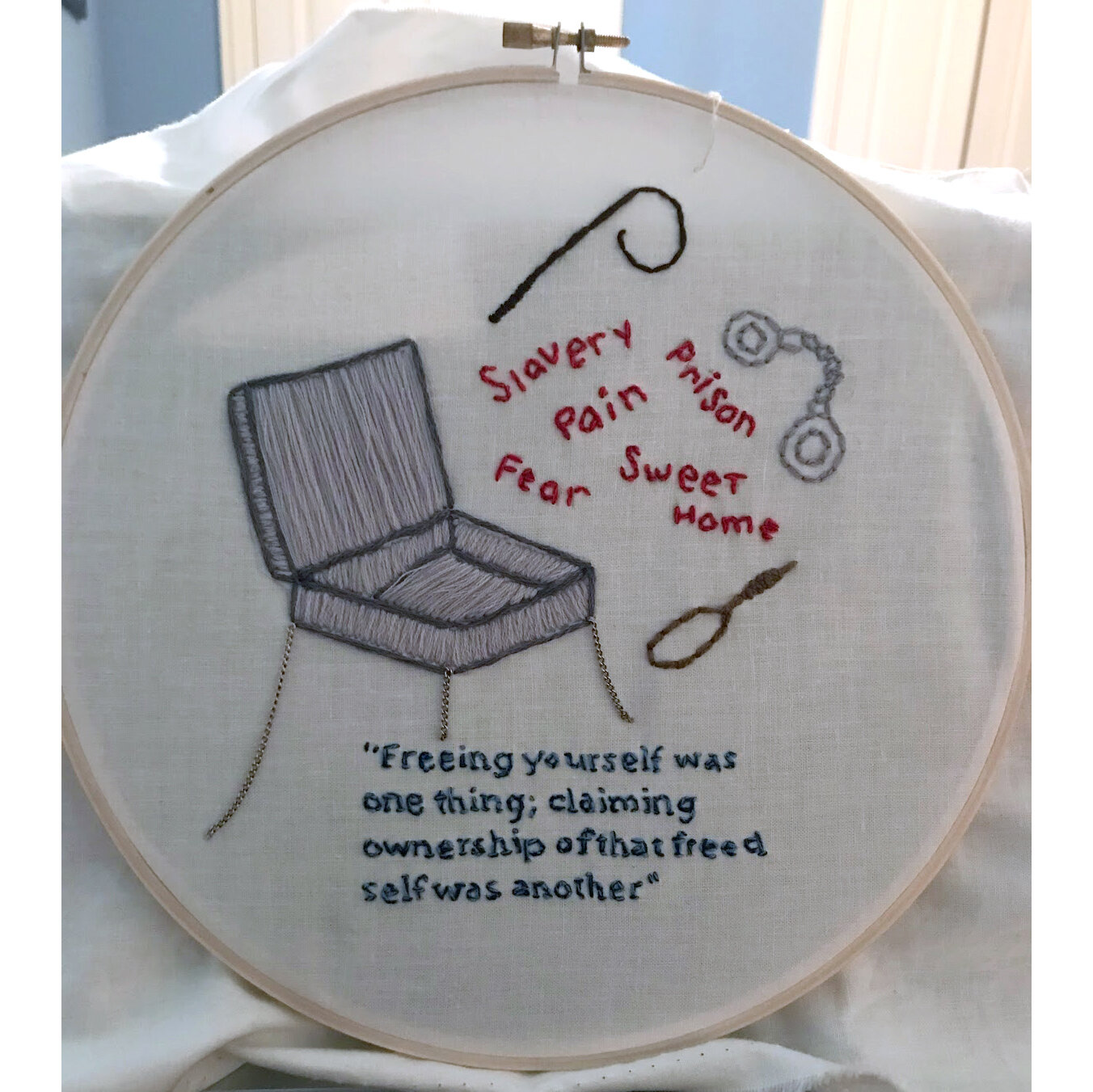

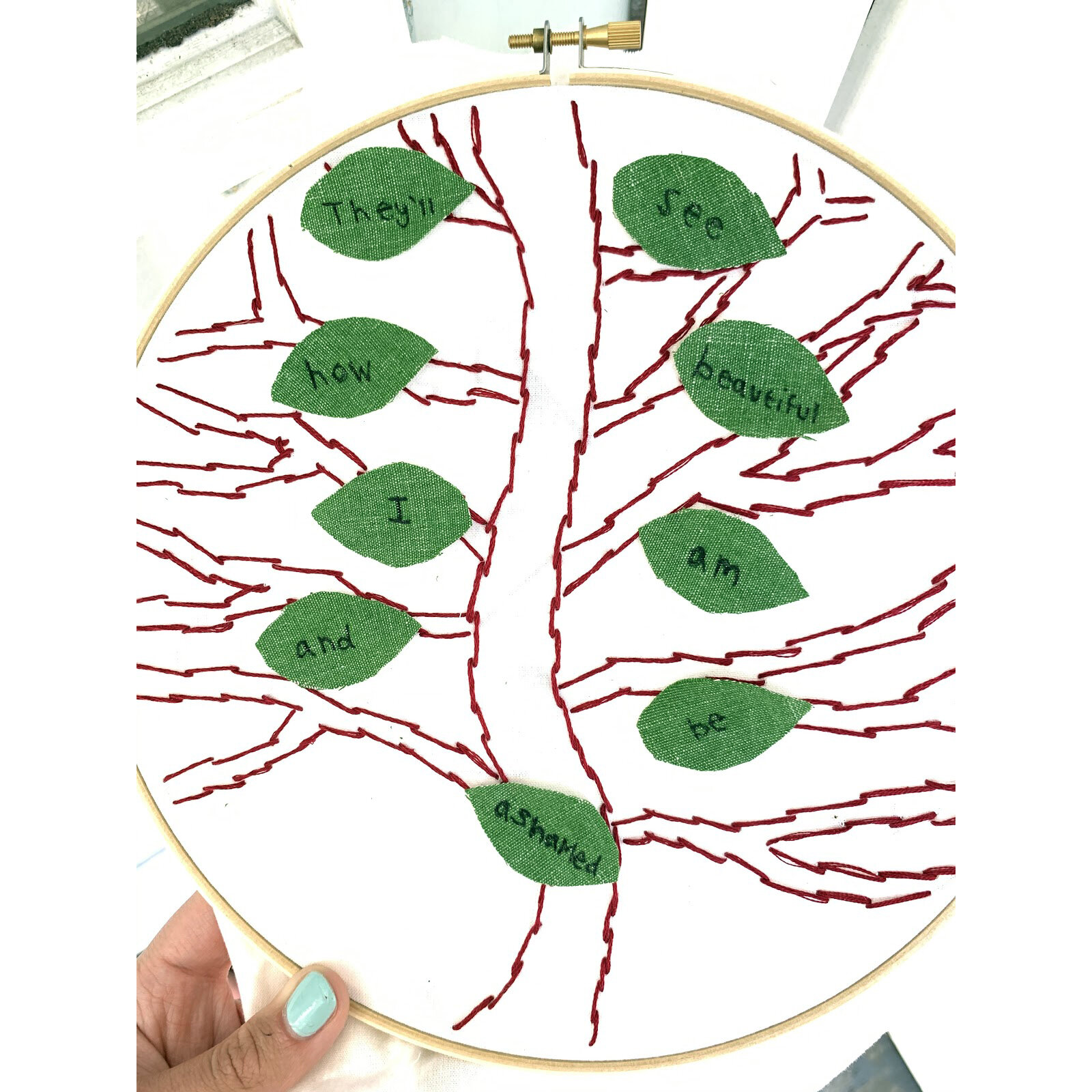

Dani H. untitled My embroidery represents the quote “freeing yourself was one thing, claiming ownership of that freed self was another.” To me, this represents how you can free yourself from where or what your trapped in but to actually feel free, you have to take control of yourself and be that strong and brave version. I embroidered this by doing a tree. Half of the tree is all neat and tidy where it says the first half of the quote. The other half is branchy and rugged representing the trauma and the devastation that was faced during this time and the lynching rope was just one of the ways that slaves were killed.

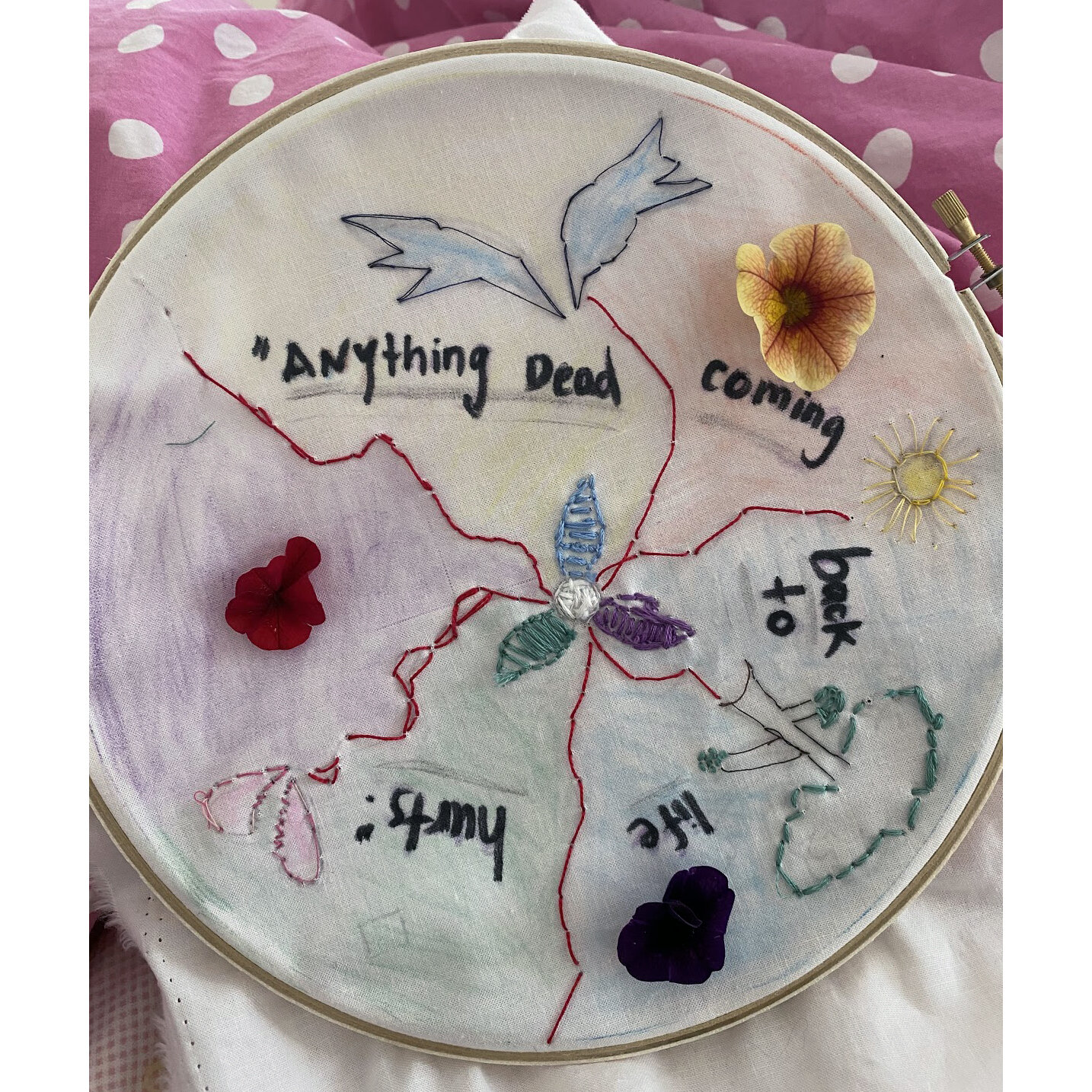

Diana I. untitled For my Embroidery project I decided to use the quote “Anything dead coming back to life hurts”.When I read the quote in the book Beloved I immediately thought about the cycle of life and what was associated with those things. In my embroidery I incorporated a flower, sun, wings, and a tree. All those things represent what is associated with life and death. A tree symbolizes the growth in life. A sun/moon are both there since the very beginning. The wings represent the after life. I connected them all with a delicate red string. The entire piece of artwork has delicate strokes, and does not really have any harshness associated. I also incorporated color because life is full of color, and although painful there is a hope. Just like Toni Morrison depicted there is hope for humankind, and the color depicts that.

Donovan G. "Eye of the Beholder" Throughout Beloved we see the dynamics of the “inner”world of 124 and “outer“ world of the rest of society. I wanted to create an art piece that illustrates this dynamic with the idea of racial trauma. The inner more colorful depiction is surrounded by a grey ring, representing the metaphor of Sethe’s eye as an iron ring. That inner area is the experiences of Sethe’s trauma of being enslaved and it is the version of racial trauma that we typically discuss. The focus flows to the pain of black Americans rather than the crimes of white Americans. Outside that ring in white thread painted white are depictions of continual racial violence that is often overlooked or even omitted from our history.

Drew L. untitled I have the red words floating out of the tin tobacco box to show Paul D’s emotions and past all coming out. I added images as well because it shows more of what is behind the words. I added a chain on the ends of the box to show that the box had been broken open, but was meant to stay closed. I chose the quote because although Paul D was “free”, he wasn’t fully allowing himself freedom because he was hiding in the fear of his past. The main idea that I was trying to get at was the emotional distress after experiencing slavery. It took me a long time to finally like my design. I changed it many times, and even changed themes. I was trying so hard to come up with a perfect design, but in reality, I would probably end up changing things during my process anyways. I think that in the end, my embroidery was a success. I’m proud of what I made. I learned that even if every stitch or line isn’t perfect, doesn’t mean it won’t turn out well. Sometimes, it is better to have some imperfection.

Eden S. "Path to Freedom"

Ellie D. untitled For my embroidery project I choose to use a quote from the book Beloved: “The future was a matter of keeping the past at bay.” I really liked this quote and it really stuck out to me so I choose to make my piece about it. I knew I wanted to incorporate a zipper in some form as my alternate material, so I choose for it to represent the border of the past and future. How the past, with all of the rugged mismatched fabric, kind of breaks the surface and emerges through to the present which is the fabric and text. I also choose to incorporate vines into the embroidery as a way to symbolize the twisted and interconnected system and civil rights and systematic racism. All in all, the idea was to represent the quote in a cohesive and simplistic format.

Ellie S. untitled I wanted to capture the aspect of both living and dead. As the quote is “Coming back to life hurts”, the left side of the price is dead. Dead grass, dead trees. It is also where I put the historical aspect. On the right, I put living things. Living tree, living grass, and I added a 3D aspect of the flowers to make it stand out.

Elsa V. "Behind the Flag" My thought process through creating my art was trying to show where America has come from until now. The civil rights images in the center present hard history that our country has overcome in order to bring more rights to the people. It also shows where we’ve started from with the American flag to the present. Furthermore, I used bold lines on the flag to show the bold movements of the civil rights movement and how people sacrificed so much to bring a better future. Also the stars represent all of the different people that make up America. Each one is different from the last and shows how unique but equal everyone is. I wanted my work to embrace the past and all the mistakes the country has made. But then I want people to take that information and put it forward to inform others and amend what mistakes have been made. I want people to take this art and put it forward to make the future a better and more welcoming place. I want people to live in a world where they don’t have to fear anyone hurting them and can express themselves.

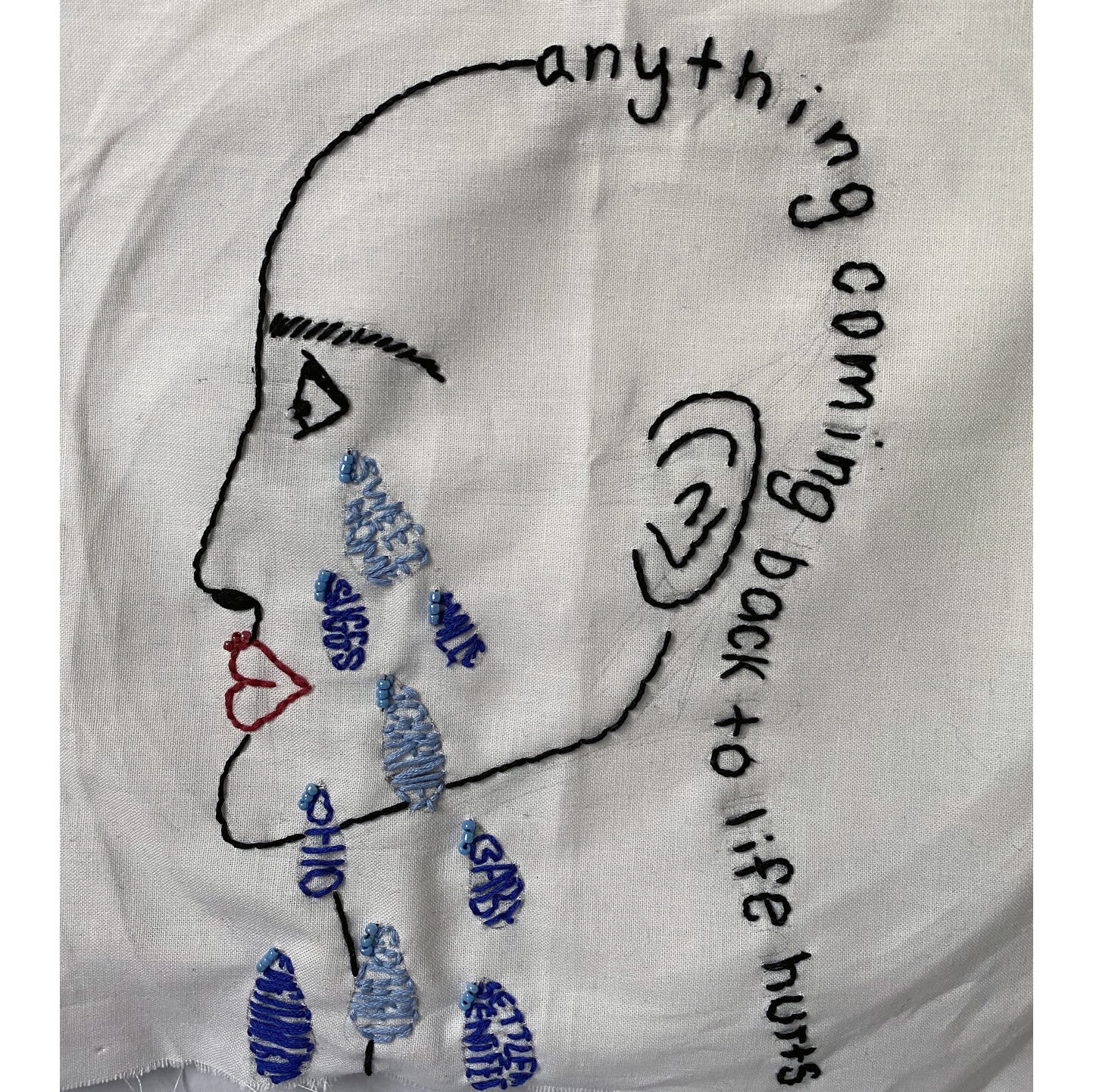

Emilia Z. "Pain of the Past" I originally had a very different idea for my piece of embroidery. I was going to take it more toward sexism and the civil rights movement and focus less on Beloved. But as we read more and more of the book, I truly began to fall in love with the sheer beauty of a Morrison’s writing. I wanted to encompass the beauty and simplicity of the writing but yet the underlying nuances, complexity and pain felt by the characters. This all went into the planning of my final piece. I chose a basic silhouette to be the main focus of my piece, a woman which is meant to represent Sethe. The main portion of the piece are the tears flowing down her face, each one of them being something that brought her pain. There range from Halle to the Fugitive Slave Bill. On the back of Sethe’s head all the way down to her neck is the quote anything coming back to life hurts. It was originally said in the book when Amy was helping Sethe in her journey. I put chose that quote as it helps encompass my theme of pain. I chose to keep the silhouette and colors very simple and add detail to the words, as I wanted to encompass that surface beauty but hidden nuance as mentioned before. I added beads as my outside material to help add light accents to the piece without taking attention away from the tears. My finished piece is meant to look simple at first but when you look closer is actually more complex, as the text of Beloved and the Civil Rights movement are as well.

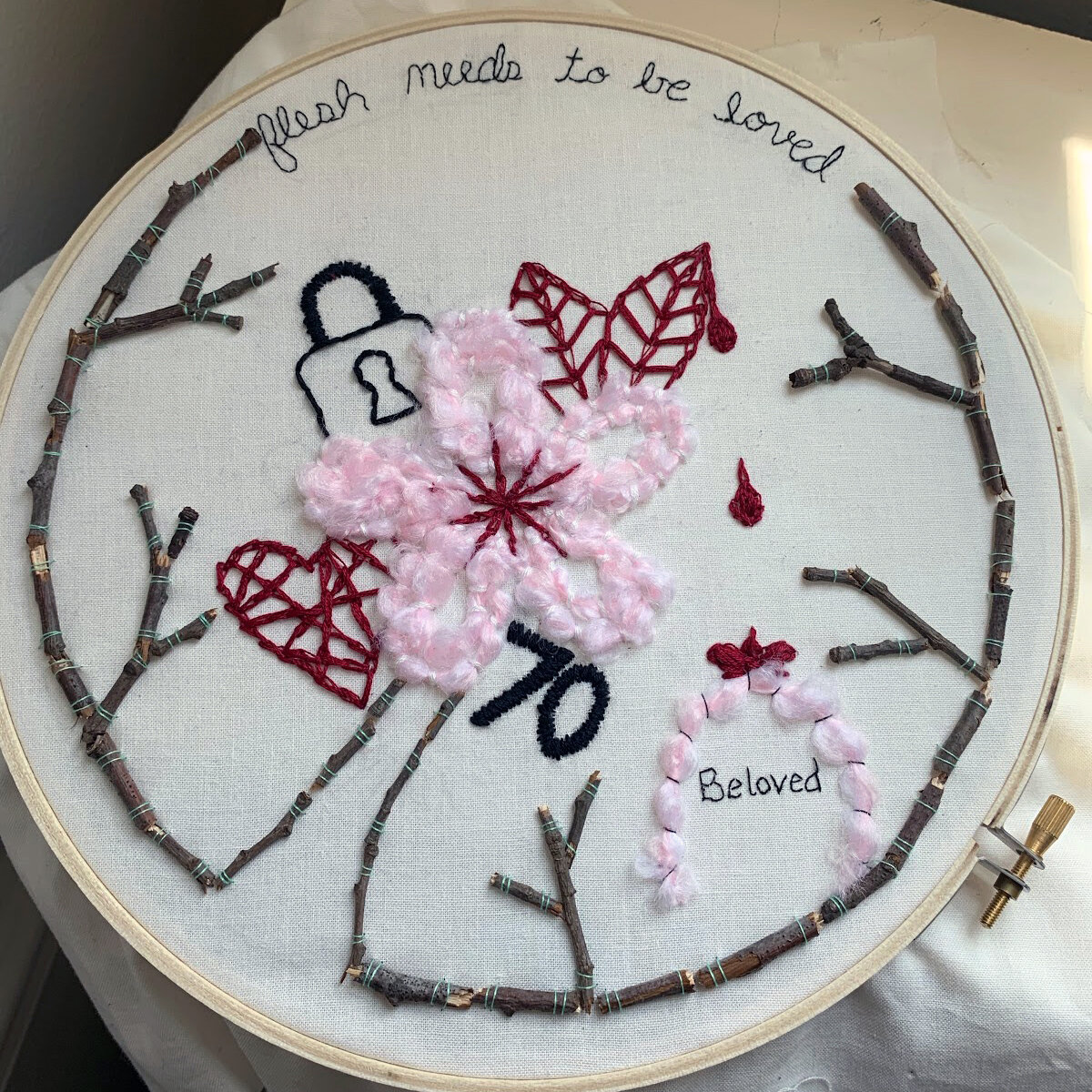

Greta G. "Seeing Color" I was inspired by how various characters coped post-slavery and the use of color, trees, and other imagery. I began with a chokecherry tree blossom in the center because I found it fascinating that although these blossoms hold a gruesome representation in the case of Sethe and her scars, they helped lead Paul D following his escape. The leaf of the blossom bleeds, releasing drops of blood that splash on the headstone with pink gravestone chips as described in the book to symbolize the blood of Sethe’s children and the blood spilt from abuse and imprisonment. After including a lock and red heart to represent Paul D’s tobacco tin, the number 70 to represent the disproportionate COVID-19 deaths that were black, and the headstone of a baby girl Beloved, I sewed “flesh needs to be loved” at the top. This is a quote from Baby Suggs and due to the large amounts of pain and suffering in the book, and dark images I included in the embroidery, I think it strengthens the idea that people need to love and be loved. The world is cruel and needs more love and kindness in it. I also sewed on fallen twigs to create branches and a tree border. I think trees are incorporated throughout the book with positive and negative connotations. While Baby Suggs was starved for color, Sethe was less affected by color around her and when she’d look at natural beauty like a tree, she would think of her back or lynched boys hanging from its branches. The juxtaposition between the color of the blossom in the middle and the branches creeping into the image showcase how trauma can force its way into people’s lives and remind them of the pain they experienced. I tried to create this contrast to portray a theme I noticed in the book; the message that suffering did not end with the end of slavery, it continued not only in Paul D, Sethe, and the other characters’ lives, but flourishes today due to the discrimination and hate still at work.

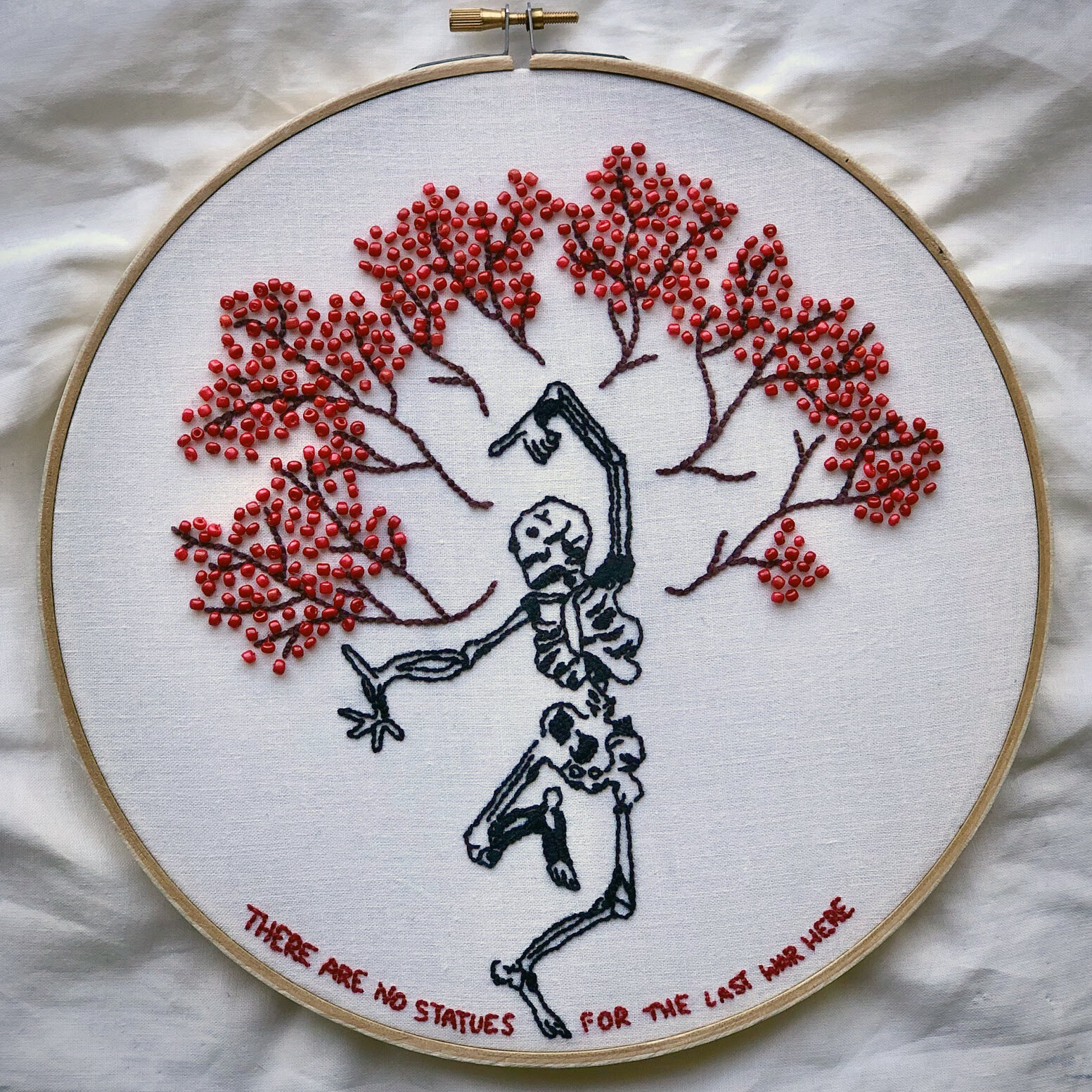

Hannah S. "America's Family Tree" I created an image of a tree with a dancing skeleton as the trunk, and a line of text beneath reading “there are no statues for the last war here”. I began my process by looking through the book Beloved and trying to identify themes and passages that stood out to me. Immediately I was drawn to the symbol of a tree which can be seen throughout the book. Most notably (in my opinion) is the description of Sethe’s scars as being like a choke cherry tree. This description lends itself to many interpretations, however the one which struck me most comes from who was responsible for defining Sethe’s scars. It is Amy, a white woman, who tells Sethe what her scars, her trauma, look like. Amy doesn’t see the scars as a gruesome result of abuse, but rather defines them as a tree full of cherry blossoms and leaves. To me this is indicative of a broader trend in which white people tend to define and defend the history of oppression black people faced. Rather than open ourselves to an attempted understanding of slavery we distance ourselves, we look at facts and numbers, we look at history books which only touch the surface, and we manage to see horrors as no more than a tree. In addition to the tree on Sethe’s back, another moment which stood out to me was when Sethe described remembering the beautiful trees, but struggling to remember the boys hanging off of them. This small moment in the book struck me harder than any other, as it was only in my second time reading it that I realized the boys hanging from the trees were not climbing them and relaxing on their branches, but were hanged from them. This misunderstanding made me hyper-aware of the place of privilege I read the book from. After rereading the sections I found relevant to my piece I began to experiment with how to get my message across. Given my past experience with embroidery I was interested in challenging myself with a very detailed piece. Eventually I decided on using the skeleton as the trunk of the tree. I made this decision to help showcase the dark roots of America. I drew the skeleton on the fabric using a heat erasable pen in case I made a mistake. I then stitched the skeleton and began to plan the rest of the piece. Originally I planned to use multiple colored beads to create a canopy as the top of the tree. However after beading for a few hours, I realized that creating the canopy was both too time consuming, and also didn’t make it clear to the viewer that the skeleton was part of the tree. After reworking the design a bit I decided to add branches and then stitch beads in as leaves. I opted to use only red beads this time around to help with the clarity of the image. I used red because of its significance in Beloved. I am overall very pleased with my embroidery, I feel that it is aesthetically pleasing, but also carries a lot of meaning and is open to interpretation. The primary theme that I worked towards for this piece was the racism that built America, and its presence in even what we consider to be beautiful.

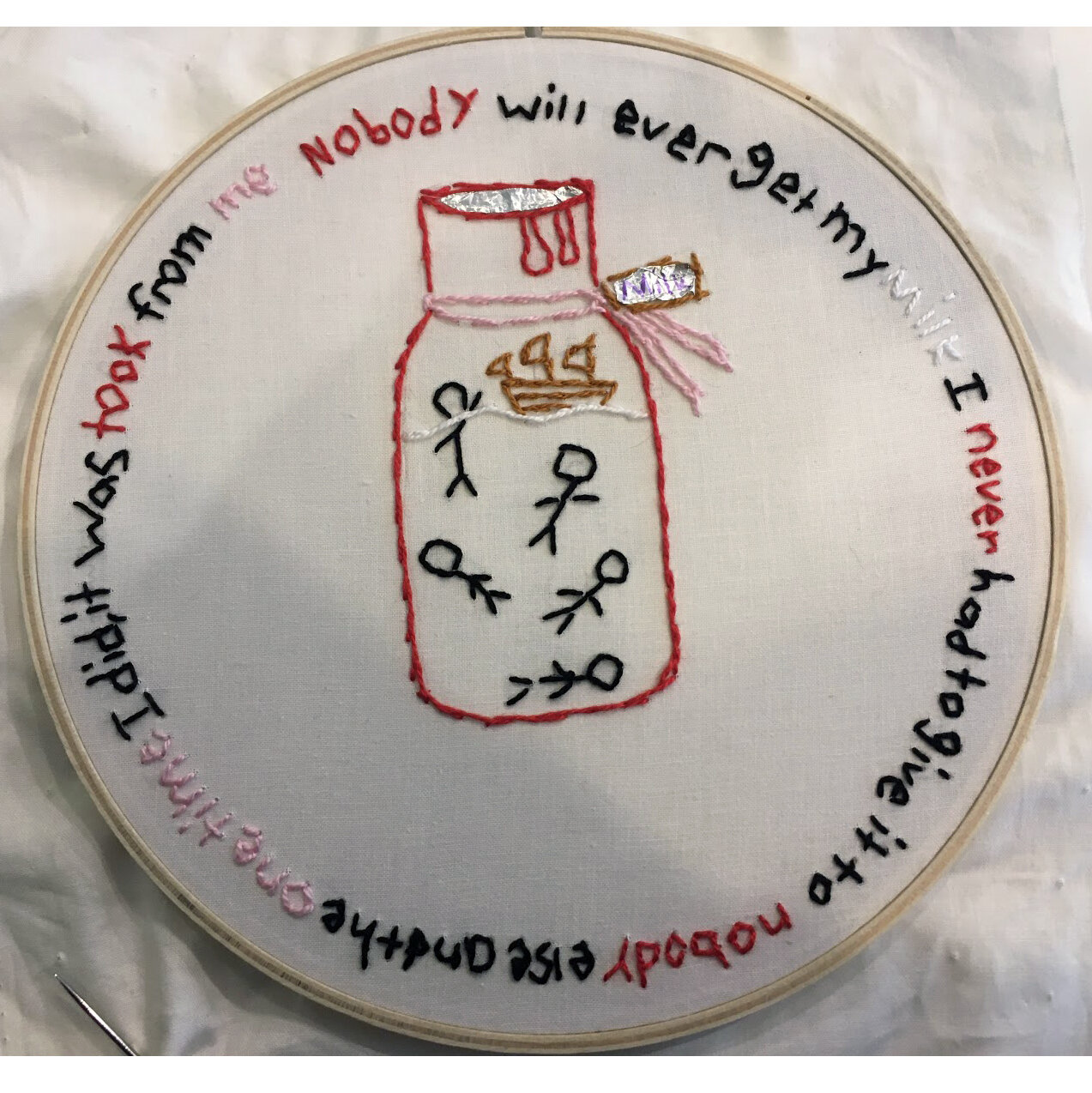

Iona M. "Stolen" I chose Sethe’s quote about her assault as my quote, as this was the one quote from Beloved that etched itself into my brain. The slave owners took every aspect of Sethe’s autonomy, her freedom, and her every choice. But the one thing they could never take from her was her ability to produce and raise life. Sure, they could take the child away from her, but they could never take away the necessary process of the early life nurturing a mother provides her child. Sethe held this one thing that she had control over, the one thing that she had for herself and no one else. But then it all changed when these white boys asserted her essentially stole that nurturing ability, essentially destroying her relationship with Denver. The milk bottle is outlined in red to represented the blood that was in Sethe’s breast milk, the blood spilling over it is to show the destruction of Sethe’s body due to her assault. The slaves drowning in the milk double as the slaves drowning in the water, but also the kids who would have died from the toxicity of the blood/milk combination. For my history/civil rights component I chose to show a slave ship gliding across the milky sea, while there is a gruesome depiction of black stick figures drowning in the bottle. When slaves were brought over, many of them would throw themselves overboard, drowning themselves to avoid the enslavement awaiting them in the US. Much like the slaves who picked the lesser of two evils, Sethe in 124 tried to kill her children in order to keep them from living out the same fate she had been condemned to. The bottle is dressed up in a misleading “cutesy” nature in order to give the audience an eerie sense of disorder within the piece. The brown thorns coming from the milk tag next to the pink ribbon represents the thorns that Sethe has grown to protect herself. The words from the quote are mostly written in a traditional black text. The way I color coded the text is meant to represent how I read Sethe’s emotions in my own head, from the passage. The shaky looking, scrappy letters represent the shaking in her voice, as Sethe holds back her tears. The red letters represent her anguish, pain, and the rising/emphasis in her voice. And finally the pink letters are a reference to her and Denver. The “one time” is referencing how when Denver needed her mother's milk the most, Sethe couldn’t provide the one thing her daughter relied on her most for. The white “milk” is just the emphasis of the “tainting” of her milk (see white waves within the bloody milk bottle). The tinfoil is one of the old fashioned ways people would cover their milk bottles, to prevent spoiling. Often times milk bottles did not come with a reusable lid. It also represents how so many africans and their descendants were sealed in their milk bottle of ill fate. An no matter how many times the “tinfoil” is removed, the milk bottle always gets resealed one way or another. Meaning racism, regardless of how many times we continue to to fight it and break barriers, it comes back in a different barrier.

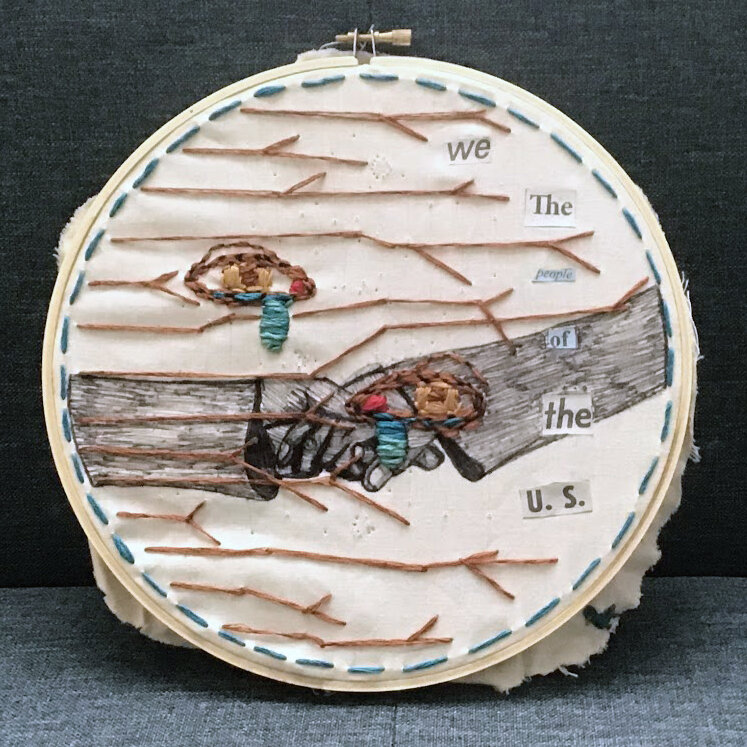

Jasmin R. "We the People of the US" The eyes resembles every eye sheds a tear. Even the strongest. The trees represents the hardship of what people had to do to be free. Then finally the hands I copied a pic of an actual protest. I thought the picture was perfect to show strong and beautiful at the same time.

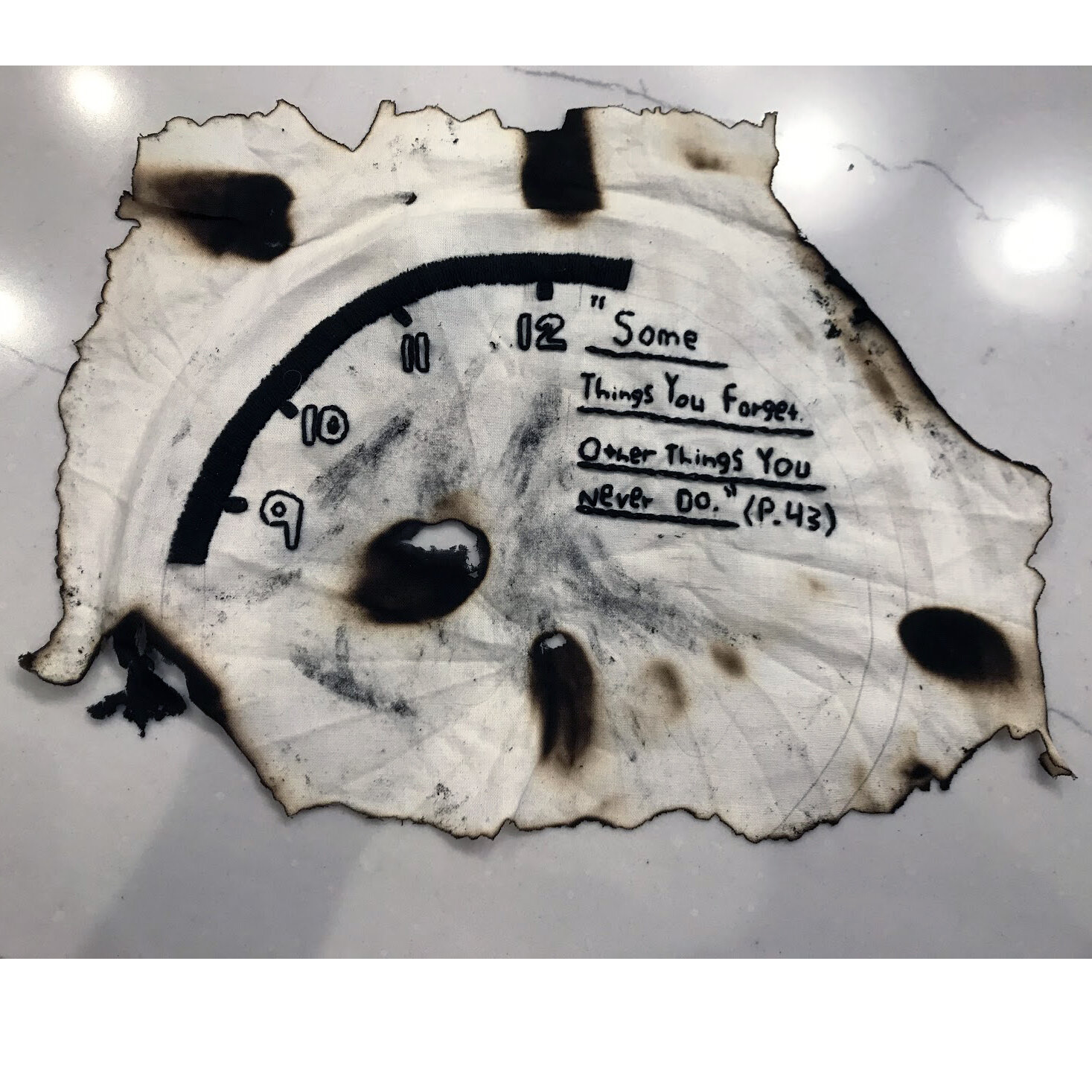

Keith F. untitled One of my biggest decisions was to use only black thread: I made this decision because it really was a case of black and white for so long black people oppressed white people continued it. Alongside that I thought the burn effect was very fitting because white washing history is so common, and most people don’t look for the real facts when they’re gone. I chose my text around the concept of time because I could relate everything this year to time. I really wanted the text to be from the book because it had more meaning to me and the other IGSS students. Also, I was very pleased with the text I ended up finding because it relates so heavily to my intended message. The idea of white washing and how some people just forget it, and don’t care to find the real answer. On the other hand some people want to know the truth which is the, “Other things you never do.” This quote is for the people who dig to find the truth and don’t let the history disappear. Since, the text was so centric to my piece I decided to also underline it for two reasons: one it makes it look more appealing, two it makes the text more bold and prevalent. I was looking for this boldness from the text because I wanted it to be the focal point. Alongside the text I had the clock. I chose to create the clock because I was always thinking about change over time all through this year. The idea that people can just let time pass and all our problems will be solved is too common. If I learned one thing this year it is that you and I have to create change. No one can create the change you want except for yourself.

Kristin M. untitled I created a an image of a person’s head that is from a phrenology diagram. I chose to do this because phrenology, a pseudoscience that involves measuring the size/features of people’s heads, has been used to justify racism, especially against black people in the United States. It is part of scientific racism, which constructed the myth that science supports the idea of racial differences among people, especially in conjunction with social Darwinism.. I thought of this idea when reading Beloved, when Schoolteacher states regarding one of the slaves, “I told you to put her human characteristics on the left; her animal ones on the right” (page 228). This quote shows how Schoolteacher was trying to use pseudoscience to justify racism and slavery. I included the colorful flowers and green vines over the head as a way to both include the imagery of flowers and color that was present throughout Beloved, but also to show how even though time has passed since these ideas were accepted, they still continue to tarnish our history and perceptions of people. I started by printing out the head diagram and glueing it on the canvas. I then gradually began to embroidery the vines and flowers. Finally, I included the text “I AM A MAN,” in red, uppercase letters as this was a phrase from the Civil Rights Movement and I think adds depth to my concept. I learned about social Darwinism and scientific racism throughout this process as well as basic embroidery and other artistic techniques. I actually started to embroidery on the background, but took out this thread as I thought it distracted from my main idea. Overall, given the fact that I am not super technically skilled at embroidery, this was a successful learning and artistic experience for me.

Lily F. "Cherub in Chains" My embroidery is of an angel, or cherub. This cherub isn’t particularly the stereotype ethereal being that we know and love, but instead a distorted version of the very peaceful and mysterious entity. Although the angel has a flashy halo with embedded gold beads, its gold-laced wings drip with red thread to signify blood, violence, mistreatment, and death. The angel’s dress is tattered and frayed, and it stands with its neck, arms, wrists, and ankles binded by chains, grounded. Because of this, this angel is forced to stay on this horrible, and unfair earth, when it, instead, should be up in heaven. Unless the chains are unbinded and the angel becomes free, it will be stuck on the ground forever. When doing a quick google search, one can discover that angels signify moral decision making, which I found to be a fitting relation, for the angel is binded by chains due to white America’s lack of moral decision making. The imagery is based directly off the poem, “For a Lady I Know,” by Countee Cullen. When I first heard this poem, I was drawn to Cullen’s contrast of two themes: one, a majestic angel figure, and the other, the dark and gruesome concept and reality/legacy of slavery. It reminded me of the white-washed, twisted, and glorified history of race in the United States we are often taught as young students, a history that tells us that what’s done is done, and there is no going back, when racial discrimination and mistreatment is an ongoing battle. Through my embroidery process, I thought about the themes of heaven and death, and that although this ‘dead’ being was an angel ready to make their deserved journey to heaven, their freedom and fighting would never be over until astronomical change occurred back on earth. I enjoyed the embroidery process. I found it to be both forgiving, relaxing, and rewarding. I think it was successful because although I don’t have a very good skill-set when it comes to embroidery, I still learned the basics and I really enjoyed doing it. I also think that I got my message and imagery across, so my work was definitely sufficient in that sense.

Lily G. "Sweet Home" For my piece, I wanted to recreate an image that had already been taken instead of making something new, because this is not my narrative to tell. I took a black and white photo of a group of slaves in a plantation field and transferred it onto my fabric, and decided to make the sky a 100% cotton tee-shirt, because all that might have been under the sky for the slaves was cotton. I also only stitched the outline of the slaves, leaving the inside of the bodies blank. This not only brings your eyes to the figures, but also symbolizes that sometimes the individual story of a slave is difficult to find. I ended up water coloring the field of cotton because a.) I was a little constrained with time and b.) it shows how the fine details of these people's lives and stories were lost within the fields and the collective story of slavery Starting this project, I think I overestimated my abilities because I had previous stitchwork experience through needlepoint I did as a kid, but this ended up being more difficult as I thought. I did find it helpful to research and practice different stitches to do in my piece, even though I only implemented backstitches in my piece. Although I did find it difficult at first, I am happy with how my final piece turned out!

Madison F. untitled My goal when creating this piece was to keep it simple. I used thin lines and very few colors. I did this to mimic the feeling I got when reading the quote that I embroidered which talked about how the beauty of the sycamore trees almost covered the horribleness of the lynchings that took place in them. I wanted to embroider the sycamore leaf because of the quote, but also because of the importance of tree imagery throughout the book. Overall, I really wanted to make my embroidery look simple, but have the ideas behind it be much more powerful and meaningful.

Margo R. untitled This piece was made to represent that slaves were so much more than just slaves. I also used the tree to represent the scar on Sethe’s treelike scar on her back from when she was slave.

Mary B. "What is Home?" I started my embroidery with the background. The background on the left is my interpretation of the type of village slaves came from. The background on the right is where the slaves were brought in America: the cotton fields. I used brush pens to create a more rustic and artistic look behind the embroidery. I wanted to create contrast between the two backgrounds, so there is a very definitive difference between them. I decided to only stitch the silhouette of the faces to draw more attention to the location of each of the faces. I used black string to represent the person I was trying to portray: the slaves. The boat between the slaves is connecting them, showing there is a connection between the two faces. I chose the words “There is no place like home” because these words are used a lot, and I feel like they can be thrown around too much. For hundreds of years, families of slaves didn’t have a place to call home. They were ripped from their original home and brought to a new place. In this new place, they were forced for work without pay. They had injustices from the beginning, and one of the biggest ones was that they didn’t have a home. That is why I added the text on the bottom. The slaves didn’t know where their ‘home’ was. I thought the embroidery was a fun project to complete. For me, it was not that hard because I have a background in sewing. I think my project was successful and I really like the outcome. I learned a lot about myself and how to do a long term project. I think you should do another IGSS embroidery project in the future.

Max B. "Facing Our Past" Personally, I’ve never embroidered anything before, so I struggled a bit at times with crafting my scene. Nonetheless, I tried my best with the time and tools that I had. My piece is intended to highlight the importance of acknowledging the past, however dark, of our nation, especially when it affects us to this day. Facing the brutality of slavery, and the corresponding inequalities that are so ingrained in our institutions and culture, is never easy, and confronting such a system may not produce immediate benefits or progress; seldom does the dominant group willingly give up its privileges out of the kindness of its heart. However, in the immortal words of leading civil rights author James Baldwin, “nothing can be changed until it is faced.” By willingly blinding ourselves to the tragic reality of our society as well as the plight of people of color throughout history and today, we ensure that injustice will continue. I used the embroidered wooden sign around the quote to emphasize this, and crafted a white hand examining it; after all, theirs’ is the group that most likely doesn’t know about the struggles of other classes, so they are the intended audience. The cotton plants growing below serve as a visceral reminder of our nation’s history of putting profit above human well-being.

Rachel G. I created an image of wings melting with wax above a flame. There are two hands emerging from the fire. The text “They Jumped” is also on fire, whereas “Leap” is embroidered in black. My process lead me to think of what materials complimented each other. For example, the burning of the fire lead me to drip soy candle wax from the wings. I wanted to incorporate two VERY different materials to reflect again the effect of differing stories. The main idea I was trying to get at was how the use of language influences how we see an event play out. You could see this landscape as wings burning and melting, or the two hands rising and growing from the fire (just as the texts contrast each other. I personally find embroidery relaxing, but very time consuming. I learned that I learned that I had more fun making it than I did seeing it at the end. Even though it’s kind of ugly to look at, I was successful at carrying out my idea and I’m glad we did this.

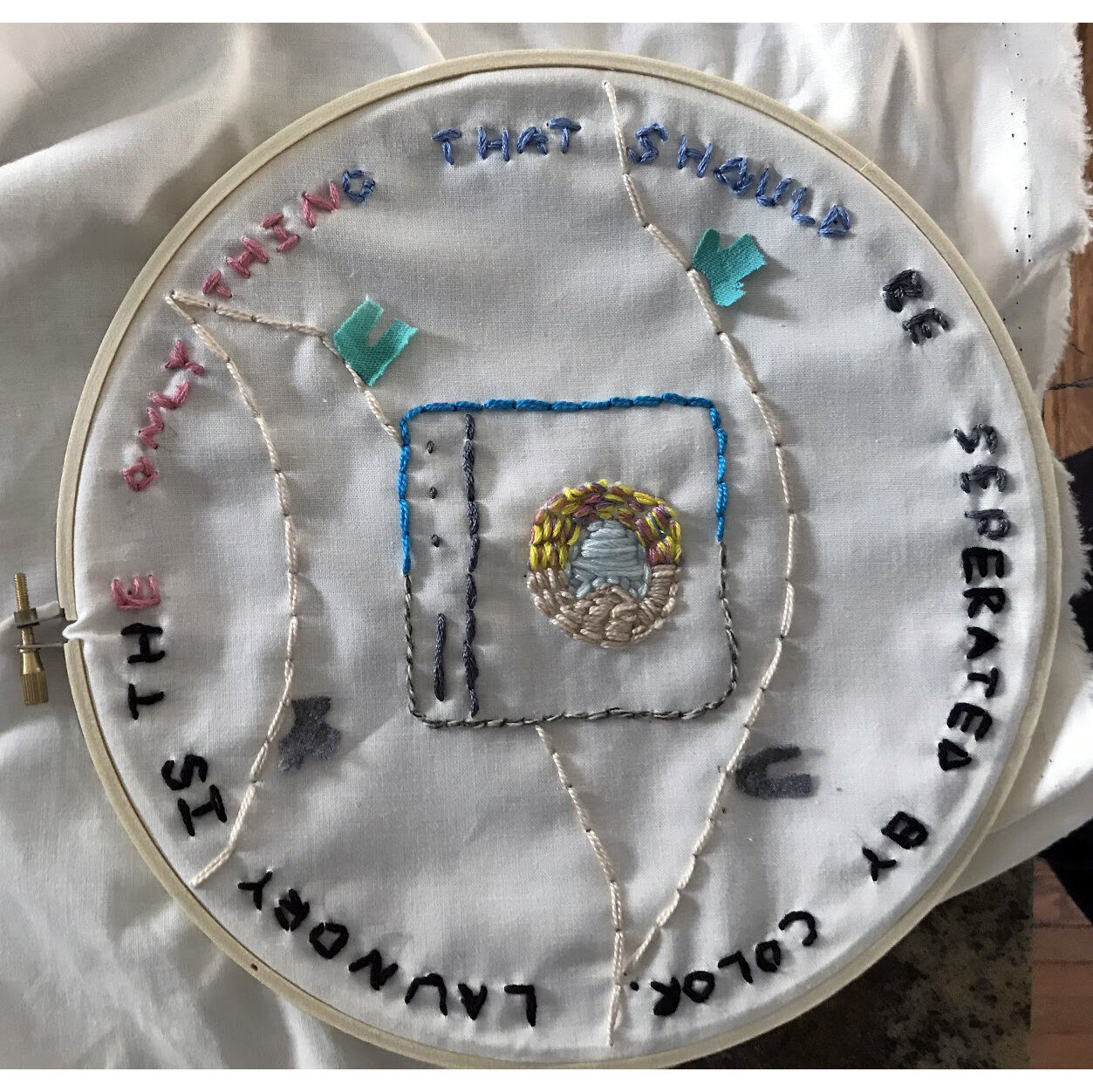

Rebecca L. "Laundry" I tried to make one side of the embroidery more muted colors and the other side colorful because I thought it was ironic compared to the quote. It also symbolizes that we have a long way to go until racism is completely abolished and everyone lives harmoniously. I wanted my work to be more of a simpler take on a huge concept that everyone would be able to understand no matter the age. To achieve this, I chose a quote that is easy to comprehend and has a metaphor that applies to everyone’s daily life. Sorting laundry is so commonplace in people’s lives and it’s hard to think that the separation of people was once so normal when in fact it is appalling. Additionally, I sewed a clothesline and used old clothes to make little clothing pieces. A rope should only be used for hanging clothes and not for lynchings.

Robbie P. untitled The text that inspired this project, which is embroidered on the top and bottom of the project comes from “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel”, a spiritual associated with the emancipation of southern slaves. The image I attempted to convey is of the sail and mast of a square rig ship coming up from the horizon. This was meant to represent both a slave ship, and a ship sailing north, another reference to the song (“I set my foot on the gospel ship and the ship began to sail. It landed me over on Canaan's shore and i'll never come back no more”). I wanted to bring to mind the use of the word “deliver” in the main refrain of the song: “Didn't my lord deliver daniel, then why not every man”. While contextually “deliver” means the delivery to a better place, under a different context, the delivery of men could represent something much darker. I am by no means good at embroidery, which is why most of the shape comes from fabric I harvested off of some old clothes. The horizon was achieved by layering dark blue fabric over black fabric. In the picture, it is difficult to see, but in person the color difference is a little more noticeable. The text turned out sloppy, which I disliked at first, but in our house critique sessions, people brought up that it complements the aesthetic, and I have now grown to like it. I am very disappointed by how the mast turned out, I really should have gone at it with a much more uniform technique, but instead of trying to cut my losses in the early stages, I decided to just keep relayering over it to try and make it look at least dense, and I only realized this was a bad strategy when I had just about run out of brown thread, and the thread was far too tangled and messy for it to be taken out methodically. However, I tried my best, and I’m not too disappointed with the final result considering my stubby fingers and lack of embroidering experience.

Sam W. "A Dirty Path to Freedom"

Sarah B. untitled I chose to use a quote from Ashley’s Sack, a piece of embroidery that was an old bag given to a former slave, and something that was talked about when the project was introduced. I chose this quote both because it directly relates to Beloved’s theme of love as well as being connected to slavery and woman who are former slaves. This quote really spoke to me and I decided that I would center my work around it instead of picking something from the book. I connected to the book with Beloved‘s headstone because Sethe killed beloved with love as her intent and wanting to save her child from harm in the future. I also chose this imagery because of the name “beloved”. When talking about names during our civil rights unit, I found it important to add this name to my piece. Though we do not know the original name of the baby, or even if she had a name before being killed, she adopted the name beloved as her own when she comes back later in the book, similar to many black people changing their names later in life during the civil rights era. I added pieces of old fabric as well as paint as to add depth and complexity when looking at the work. One of the fabric pieces looks like burlap, which was the material Ashley’s Sack was made of.

Sol Q. "What is America" This piece of embroidery is inspired by the contradiction of so called “ classic American values” and the harsh truth of systemic racism. The question WHAT IS AMERICA at the top of the piece is presented as a statement. It is at the top and is the largest type in the piece, imploring the viewer to question for themselves what America is and what we stand for. On the right and left sides there are human skulls with names written into an outline. These are the names of individuals that were murdered in the name of racism. Some were murdered as a result of their civil rights involvement and others simply because they were black. Underneath the skulls I’ve written “And all that were not named” to pay homage to the people who were murdered and their bodies never found, from those lost in slavery and to the police brutality cover ups of today. In the center there is the skull of a bald eagle. America’s national bird. The Bald Eagle nearly went extinct, a fact that seems ironic considering the symbolism of the bird being synonymous with American values. I also chose a bald eagle skull to indicate that the values and symbols America holds as the forefront of society- freedom, justice, and bravery- are not actually in action. Hundreds of years of oppression, murder, and lies, have created a hypocrisy of a country. Hanging from the Eagle’s beak there is a silver laurel in a fabric of leather. Laurels were used in Ancient Greece and Rome to represent honor truth and victory. The last feature I added to this piece was the water colored red blood stains. I wanted it to confront the viewer, to be a feature that you could not overlook. The blood represents the lives lost and blood spilled to fight for the America all people deserve. The blood of those that died fighting to end slavery, to desegregate, to protect the right to vote and all of the other human rights that are denied to those with a different skin tone.

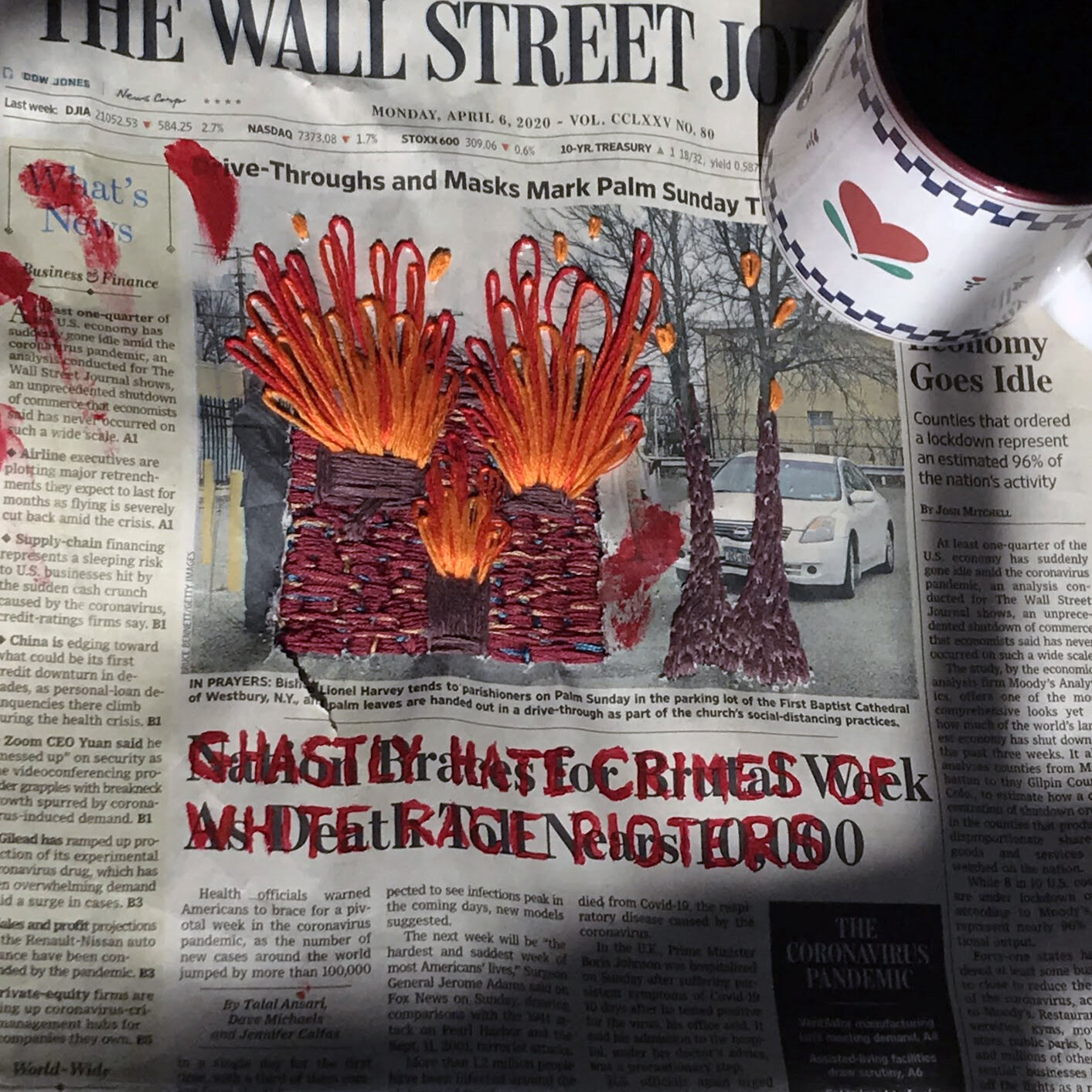

Stevi B. "Real Red Summer" For my piece, I embroidered a burning house and trees onto a newspaper to represent the hate crimes committed during Red Summer. I chose a current news article about coronavirus to compare the world events that occurred then versus now, and ideally I wanted one that also compared the unequal treatment of black patients versus white patients, but I couldn’t find one so I just used one that brought up the death toll of coronavirus. I tried to depict how the past and future are connected by only embroidering the bottom of the trees and having them transition into the trees of the article, and I painted over the preexisting headline to make it harder to read so the viewer would have to really focus to make out which word went with which heading. I also decided to paint on my altered news heading in red to emphasize the brutality of the acts committed during Red Summer, and included red fingerprints to make it look like blood smeared on the page. I wanted to depict the reality of Red Summer in my embroidery because it’s an example of the clear white on black violence of the Civil Rights era. However, as I was researching old newspapers I noticed that a lot of the headlines made it seem like there was equal amounts of violence coming from both black and white people, even though it was white people initiated the race riots and committed hate crimes against black people, and that responses were in defense. One article that stood out to me had the title, “Ghastly deeds of race rioters told” and I thought this didn’t accurately represent the situation, so in my art piece I switched it to, “Ghastly hate crimes of white race rioters”. I was inspired by Alexandra Bell in my process because of her work with redoing current newspaper articles about race and how they often criminalize people of color, even in situations when white people are the perpetrators, and how this can influence readers and perpetuate bias and racism. I’m proud of my embroidery because I was able to experiment with a material and prices that I don’t normally engage with and I communicated my ideas how I envisioned it. In this project and throughout our year of art, I’ve come to appreciate the process of making art and now understand how dynamic is can be, and that the process itself is as much a part of the art as the final product. I think this project was successful because I was able to alter my vision and revise my work as I made the piece, and overall had fun with it and I like what I was able to represent.

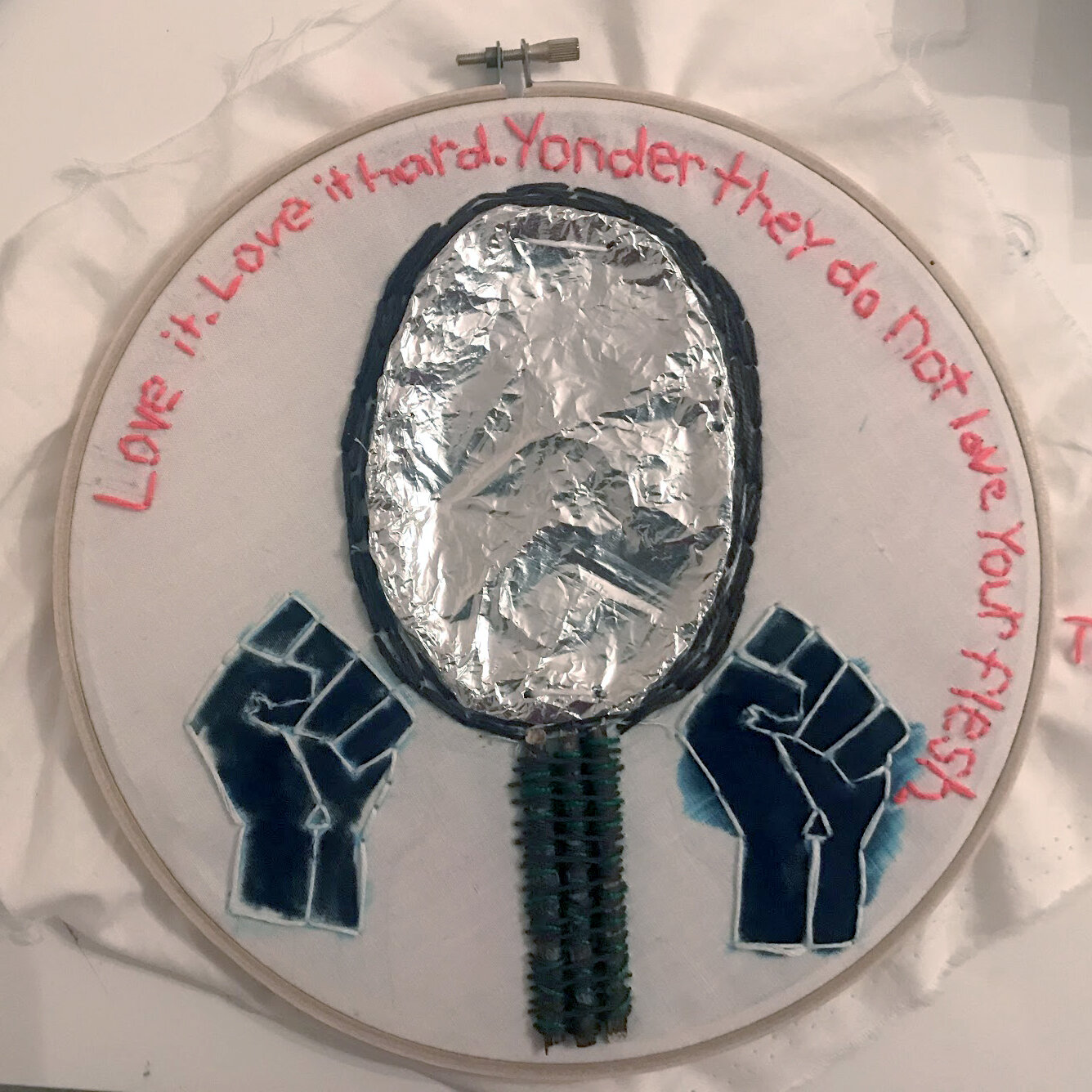

Tatum M. "Reflect" In my embroidery I was inspired by a quote by Baby Suggs, where she says “Love it. Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh”(103). She says this to the people in the clearing in the forest and to me, this whole page and quote is saying you are free and you need to love yourself, love who you are and don't let anyone put you down again and make you feel inferior. This quote directed what my embroidery looked like. In the quote it says “Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh.” I saw it as white people disrespecting black people. The white people made the black people slaves and brutally punished them by whipping them. The whippings left scars both internally and externally on the body. So I decided that I would embroider something that had to do with reflection; looking both inward and outward. I ultimately decided to create a mirror onto my canvas because Baby Suggs is telling the newly freed slaves to look at themselves and to love who they are, instantly I thought of a mirror. For the mirror I used tin foil and the tin foil/mirror is meant to represent healing and loving yourself even though you may feel or look damaged from slavery but it is showing strength. The mirror is also a symbol of reflection that shows you that you are your own person and no one can control you again because you now have dignity and new found self confidence. The handle of the mirror features woven in sticks; the sticks for me represented trees which were a big symbol in Beloved. The sticks were from my yard and I wove them using green and brown string. Another reason why I had used sticks was because they represented life and hardship and ultimately the journey to freedom. As my civil rights aspect to my embroidery I chose to embroider an outline of a fist in white and then I colored it in using a black marker. I chose to do the black power fist because it represents unity, solidarity and justice for black people. The black power fist was commonly recognized and symbolized in the 1968 Olympics. Where Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the first and second place winners of the 200 meter race, who were also African American. This event is remembered because it was a powerful moment in history. Upon receiving their medals, Smith and Carlos each put up a black gloved fist, to show solidarity and resistance in the face of a number of human rights violations, in the Olympics. This was done during the national anthem for all of the world to see. The black power fist was also commonly used during the black power movement and the Black Panther Party in the 1960s.

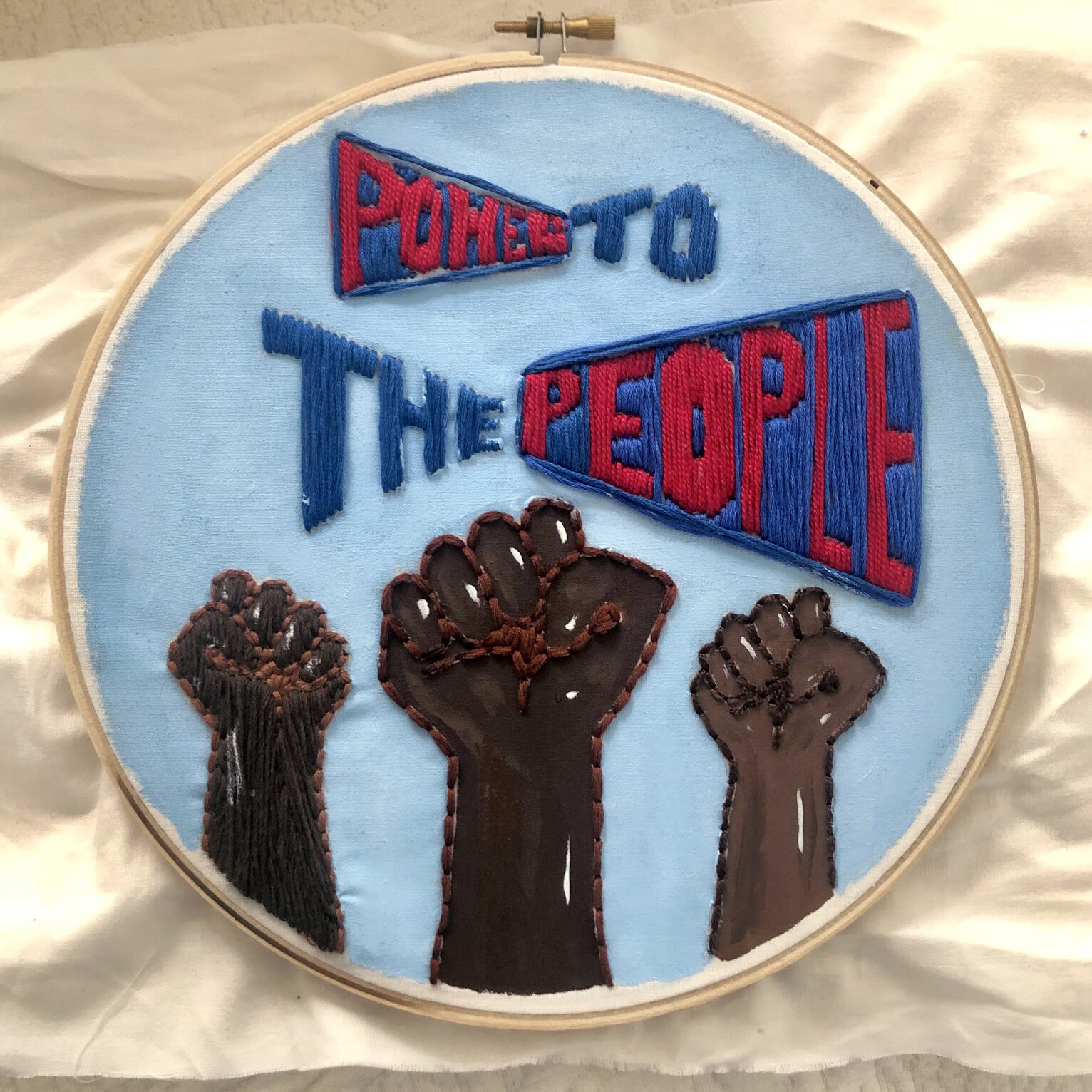

Uma F. "Power to the People" For my embroidery project, I was inspired by posters from the civil rights movement. These posters were filled with bright colors, bold, fonts, and strong messages to help spread the movement. One aspect of the posters that I especially wanted to include in my embroidery was the raised fists. During the movement as well as today, these raised fists were used to represent unity or solidarity. Overall, I wanted my embroidery to serve as a representation for the demonstrative acts of rebellion against institutionalized oppression that occurred during the civil rights movement and continue to occur today. As part of my process, I used various colors of embroidery thread to create outlines for my text, “power to the people”, and the raised fists. I filled in all of the text with embroidery thread, and I used sort of a color-blocking method to add to the overall “poster-look”. I used the colors blue and red not only to add contrast, but also to add to the whole message of power. I was planning on filling in the raised fists with embroidery thread as well, however, I was having a lot of difficulty doing so. This is where my alternate material came into play: acrylic paint. Not only did I use acrylic paint to fulfill the requirement of an alternate material, but I also used it to intensify my project. I found that using the acrylic paint was a good way to incorporate more texture and boldness in the work. I also used acrylic paint for the background, to tie everything together. Overall, I found that embroidery was a very confusing yet fun medium to use. I found myself to be extremely frustrated with it at times, but in the end it all worked out. It really taught me to be more patient and “trust the process”. I think this was a successful project because I think it truly communicates the message I wanted to convey from the start.

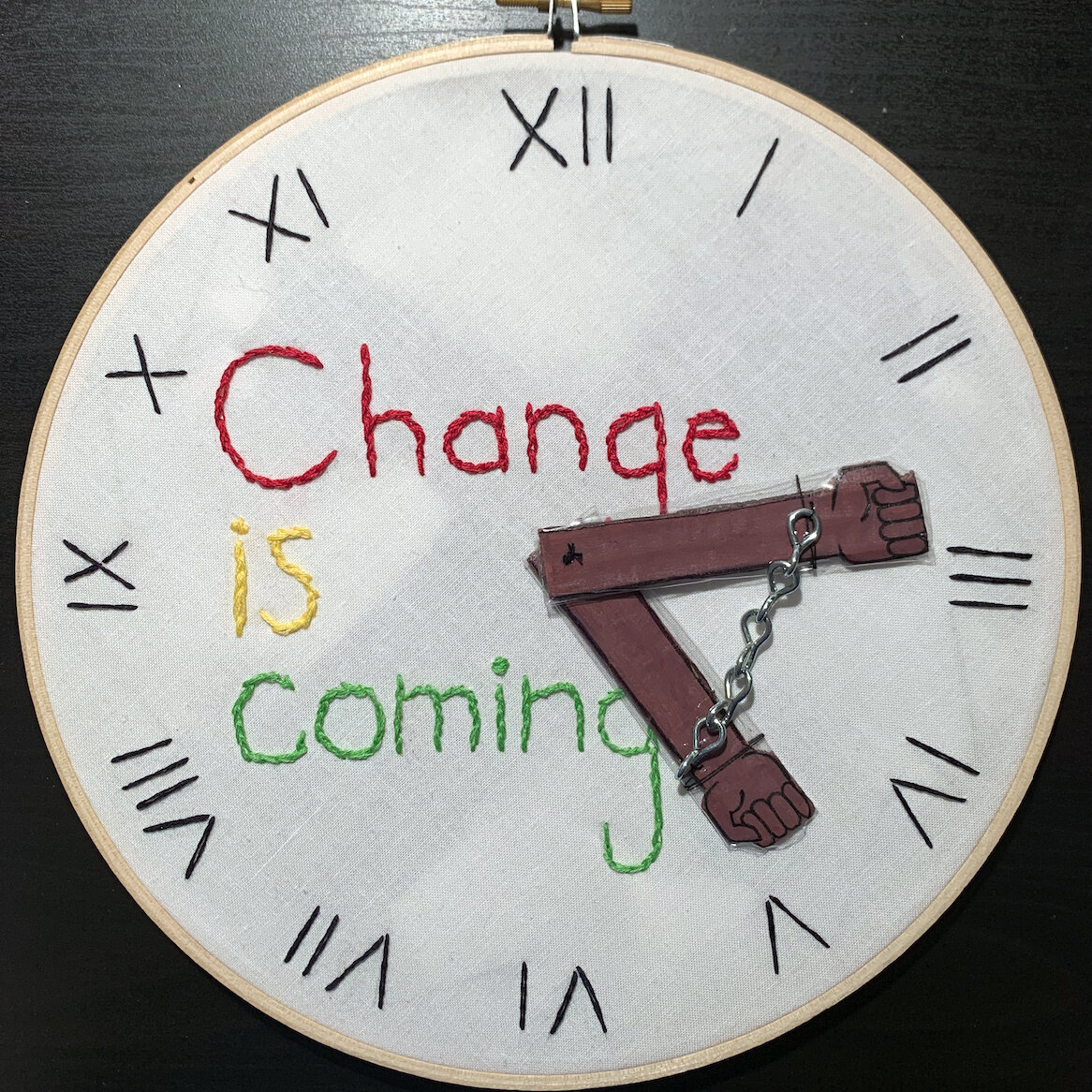

Victoria C. untitled For my embroidery, I made it so the whole hoop was a clock, with the numbers in roman numerals and with a black person’s hands in chains as the minute and hour hands to symbolize slavery. To create this, I first sketched everything out in pencil, then embroidered the numbers, then I did the text which says “change is coming”. The text is to symbolize how with time, changes in laws and society are to occur, such as the abolition of slavery and the civil rights movement. Afterwards, I made the hands out of cardboard, painted and shapried them, then covered in tape so it would be smooth. Then I went to Home Depot and bought the smallest chains they had and attached them into the hands. Then I sewed the hands to the center of my embroidery piece so it would come together, and the hands are still moveable. For the image I submitted, however, I tried to make the time read 2:25, which is meant to translate into page 225 of Beloved. On page 225, there is a quote saying “...but schoolteacher beat him anyway to show him that definitions belonged to the definers--not the defined.” This is another representation of slavery’s horrific past, but how change ultimately comes. Now, the definitions belong to the defined, or are at least on that path. With embroidery overall, I enjoyed the project and it was nice to do from home. I think it was successful overall and I’m pleased with the way mine came out, even though it isn’t super intricate. There were also times that I made mistakes in the embroidery, but I was able to pull the stitch back out and redo it. The process takes patience, but it comes with a rewarding outcome.

Xariah Chase "Fallen People, Solid Rock" My embroidery endeavor complimented the sojourn of reading Beloved by Toni Morrison. From the moment I read about “The Clearing”, I could sense that it wasn’t just a place, or a weekend escaped for the Black community. Furthermore, “The Clearing” was not a person, although Baby Suggs personified it for the better part of her life. As a result of my captivation with “The Clearing”, my first puncturing into the embroidery cloth was the outline of a rock with thin gray string. I later filled the rock full of silver, which adequately captures my ideas of the rock on which Baby Suggs Holy prayed silently. Baby’s faith reminded me of my own, and the rock related to a common saying about God. In the Bible, the psalms say that God is a rock. This means that God is not only strong, but He does not change, He cannot be moved. God’s kindness and mercy never change. God never fails. He is solid, strong-standing, and powerful. The events of life makes this concept hard to grasp, and Baby Suggs Holy’s loss of faith in the face of her reality does not surprise me. Still, this does not alter God’s standing as a rock for generations. Baby Suggs Holy’s life and death were central to my interpretation of the key events in Morrison’s story, especially the slaying of her grandchild, Sethe’s young daughter. This is why the unmistaken red blood appears on the cloth, and spills into Baby Suggs’s heart of hearts. The choice to represent Baby Suggs as a mountain came later in my reading, as her past is revealed. The stitching of the mountain is intentional marked and obvious, showing the many pains that Baby Suggs have defined much of Baby’s life. The aftermath of the horrors that took place when Beloved was slain left Baby Suggs Holy, an upstanding pillar of a woman, loosely tied to the rock which she used to be. This is why I chose to expose the ties of the thread on the presentation side of the embroidery cloth. “Her faith, her love, her imagination, and her great big old heart...” were stained with blood and betrayal. But the rock still remains. Overall, I decided to depict objects, ideas, and nature rather people. I found that Morrison’s literary focus is on memories and their impact on one’s mental, emotional, and physical landscape. The civil rights element I chose closely connects to Baby Suggs, the mountain. Like MLK. Baby Suggs has been to the Mountaintop. Reverend Dr. King declares: “I’ve been to the mountaintop” and “I’ve seen the promised land.” Baby’s life was painful to say the least, but she has plenty of revolutionary, mountain topping periods in her life. She was able to have an incredible impact on her community and help them see light, love, and grace they wouldn’t have otherwise known. Despite this, Baby Suggs, as well a MLK meet a tragic end that sends a ripple effect out into their spheres of influence. Yet again, they have known the freedom of the promised land ~

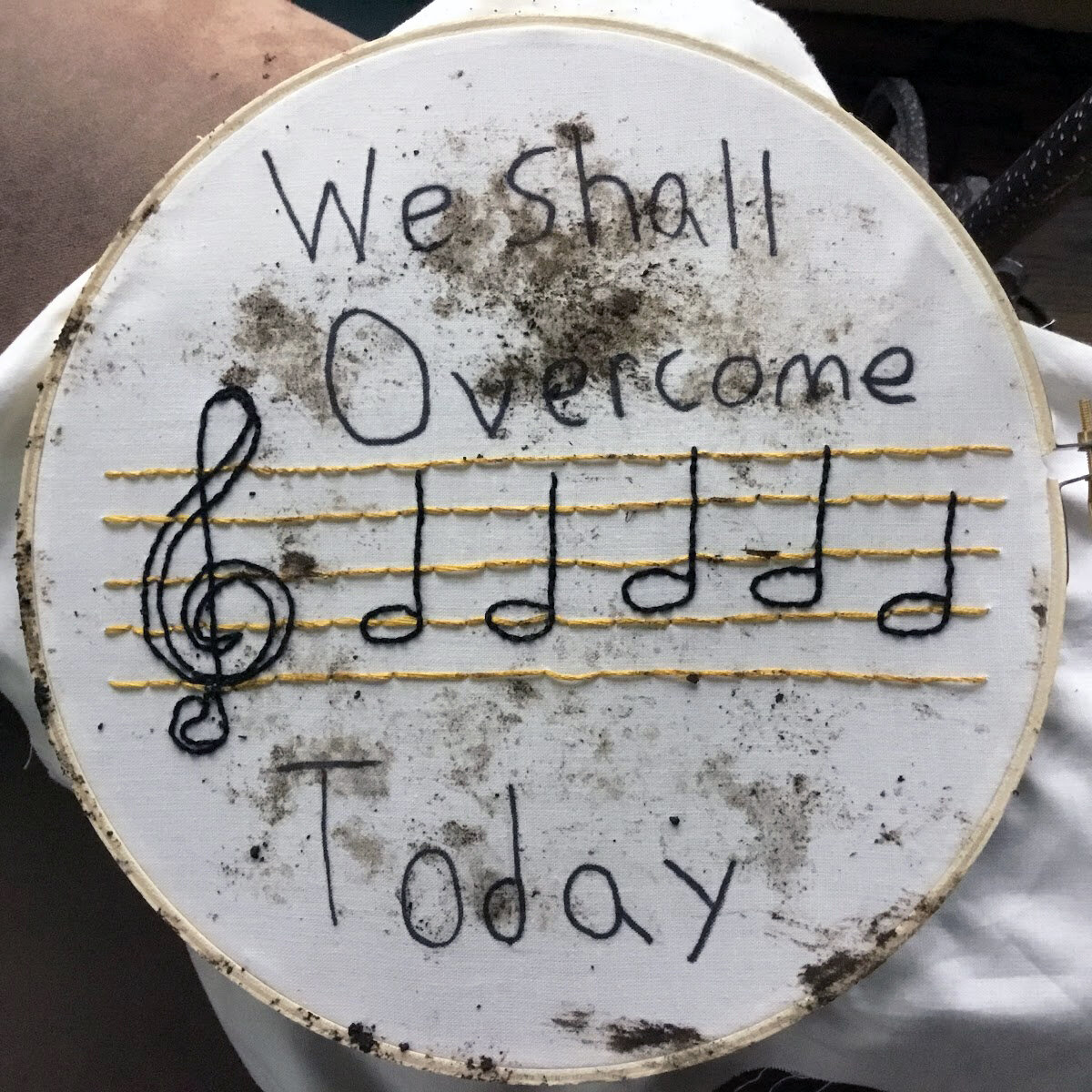

Hillary C. untitled The words “your storied will not stay untold“ were inspired all of the new knowledge that I gained from our Civil Rights studies. I learned so many essential stories about black history in America that I had never heard before, and I am frustrated that such an important part of our country’s history was never revealed to me. I do not want these stories to stay untold. The neon orange thread for the word ”untold” was used because orange is the most visible color, and the stories of black people in America should be seen. The paper underneath the word ”untold” is used to further emphasize the fact that this part of history needs to be told. In Beloved, the symbol of a tree was used throughout the book, to describe Sethe’s scars, as well as a symbol of death because victims of lynchings were sometimes hung from trees. In my artwork, I placed a gravestone under the tree to show how even though a tree can symbolize life, it is also part of a painful history. The book is a reference to the fight against segregation, especially in schools. The fire references the endless violence against black people and their movements to fight for freedom. I thought of the massacre where entire communities were burned down, or houses and churches bombed. The music notes and the circular design are references to the art we studied from the Harlem Renaissance..